The president of DRP Masonry in Louisiana is determined to do as much for masonry as it’s done for him.

Ask Donnie Williams, president of DRP Masonry, to distinguish between what he wants to do, and what he needs to do, and he’ll say there’s no difference at all. Both are naturally baked in to the five-generations-deep business that runs through his blood and keeps him going every day – brick-laying.

Masonry has seen Williams through extreme thick and thin. When a heroin habit in his 20s helped him run a business into the ground, brick-laying was there for him after he got sober and began recovery.

With Williams’ harnessing, his Monroe, Louisiana-based masonry business has generated livelihoods for not just one person but dozens of employees – including brothers, uncles, nephews, cousins, sons, daughters, and non-family members Williams treats as family too.

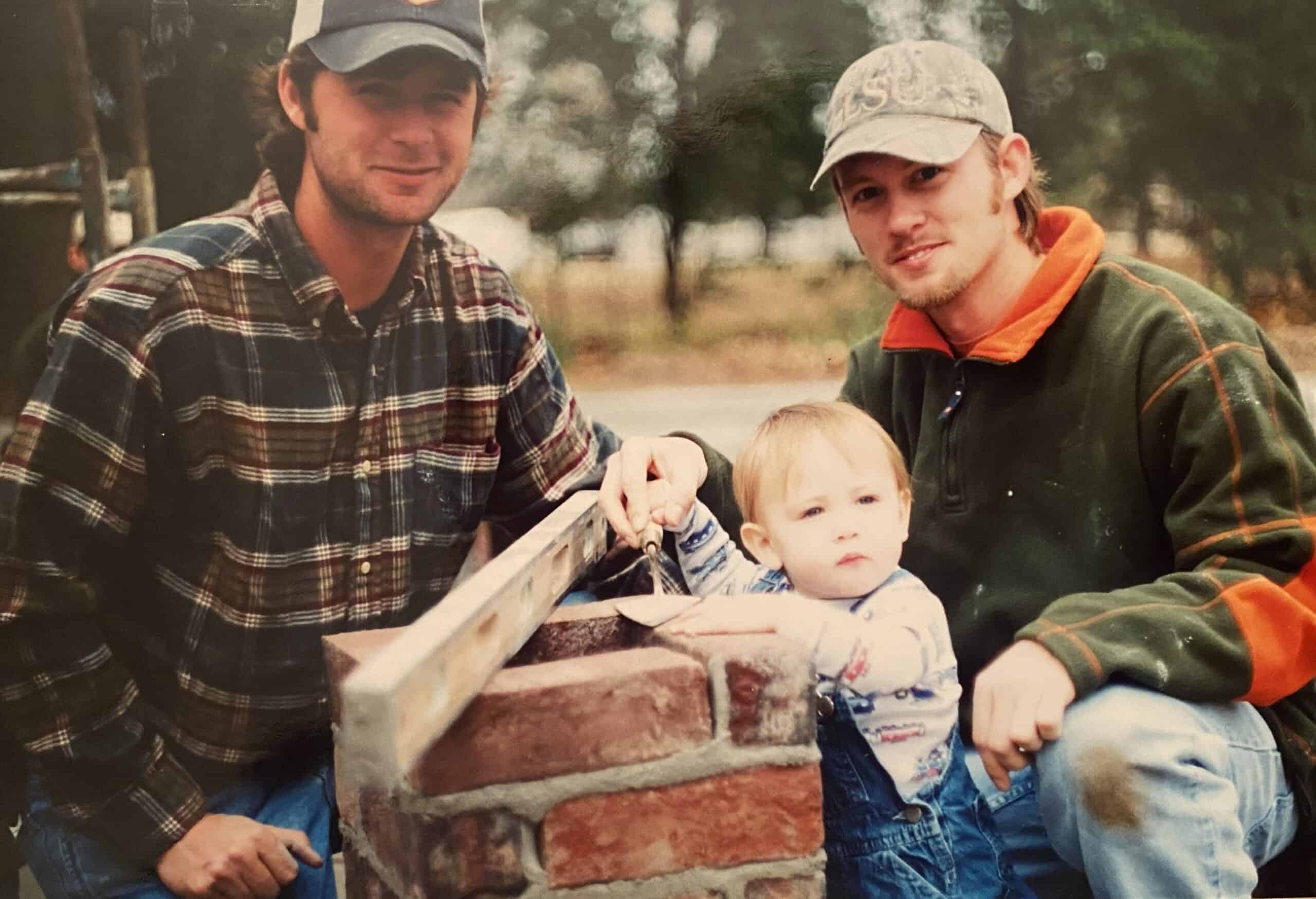

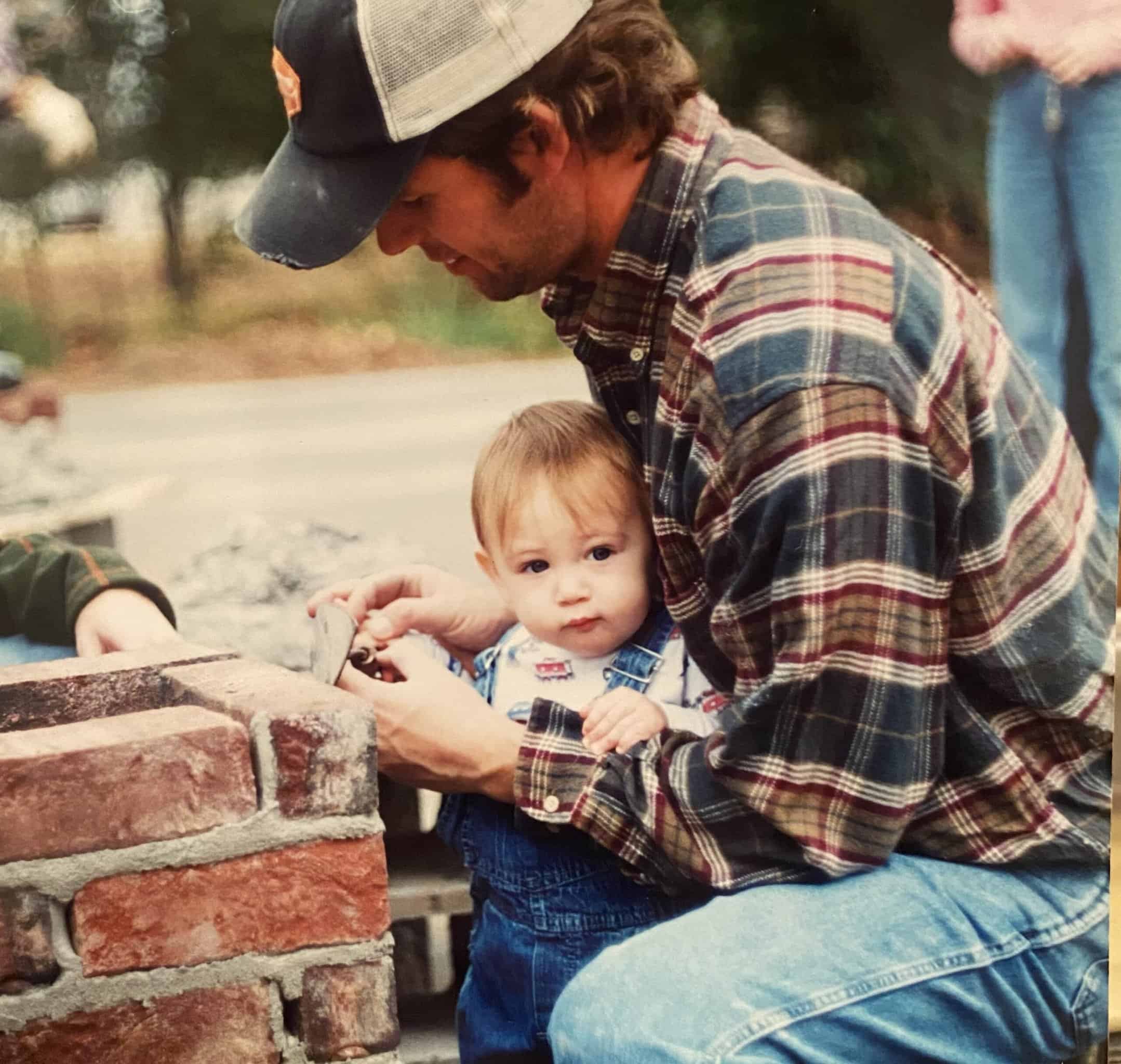

A history molded by masonry is what has kept Williams feeling responsible for the brick-laying legacy staying alive through his children, his children’s children, and every generation after that.

Masonry is the birth right that awaited Williams’ youngest son on his first day on the planet – he was christened with the middle name “Brick,” which the now-5-year-old goes by today.

Masonry was perhaps the only, and the exact thing Williams needed to challenge himself to keep going and growing to new aspirations all the time – goals that Williams keeps kicking further and further away, insisting they remain out of reach as they grow bigger every day.

Extending a long legacy

Williams, 48, could retire today, but he doesn’t want to. He wants to keep working (until age 70, he says). He likes it. And besides, he needs to stick around long enough to make sure someone comes up through the ranks to take over the business he and his siblings bought from their father, Don Williams, in 2013, and subsequently grew by 15 times in less than a decade.

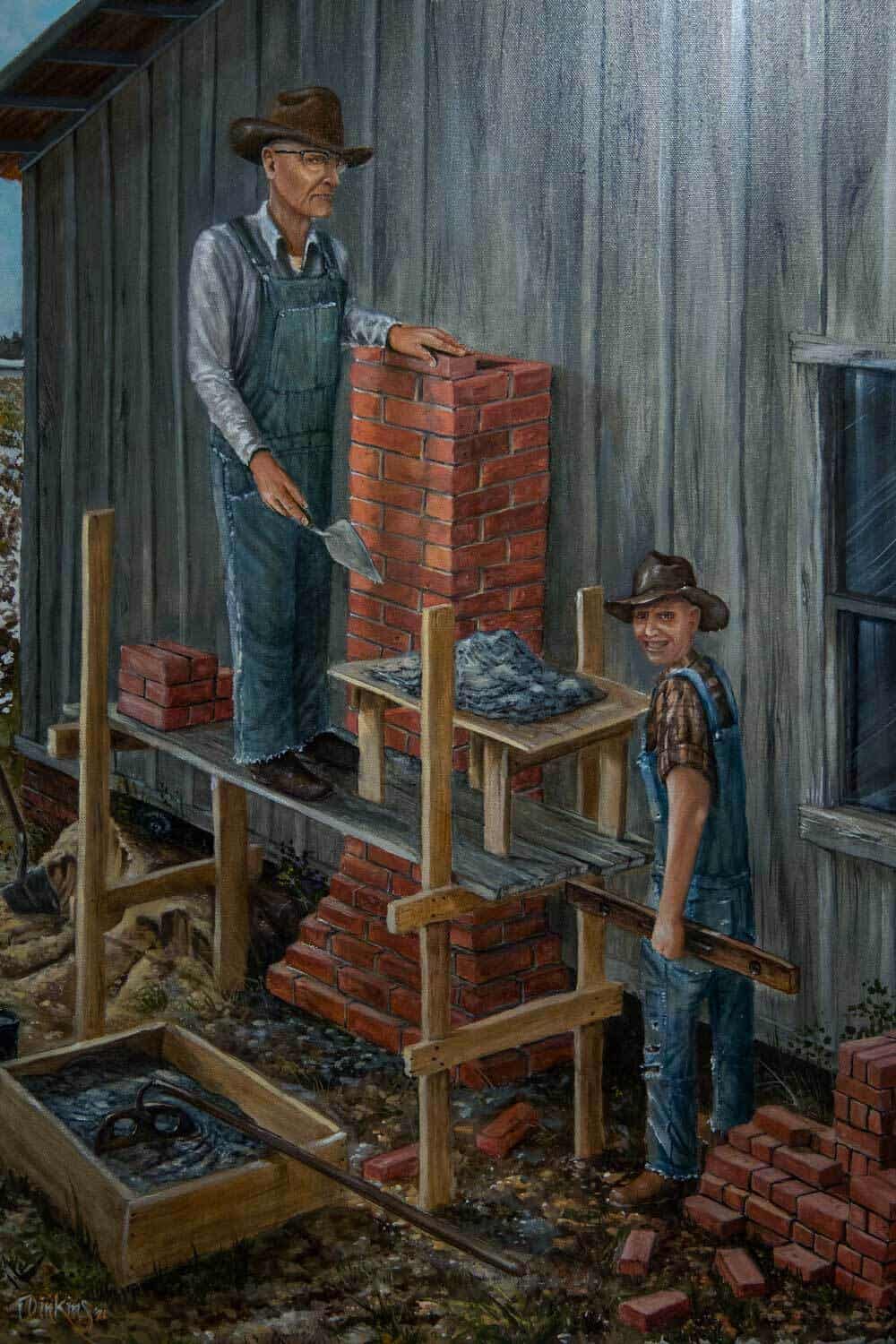

His brick-laying heritage goes much further back than his parents. It was Williams’ mother whose grandfather was Clayton McVay (known as Paw Mac), a sharecropper in Deer Field (now known as Delhi), Louisiana, in the 1920s. Paw Mac and his wife, Crittie McVay (known as Maw Mac) had 13 children. Paw Mac soon realized that farming wasn’t going to cut it to provide for his large family. He picked up the masonry trade and started building chimneys in his town at the start of the Great Depression. Paw Mac’s son Curtis, born in 1928, picked up brick-laying and became a local legend at the trade. He founded Curtis McVay Brickworks.

Don Williams (Donnie’s father) married into the McVay family, practically requiring him to learn how to lay brick. He took the initiative to get the business onto larger commercial projects and, in 1986, obtained his license to perform work over $50,000. He created Williams Brickworks. Along with his brother Dennis, they started doing hospitals, schools, and prisons in north Louisiana and north Mississippi, and grew to an annual labor and equipment total of $1 million.

Don turned the business over to his sons, Donnie and Philip Williams, who formed DRP Masonry in 2013.

It wasn’t a period without tumult for Donnie. Before he could focus on the business, he had to face his own demons once and for all.

In his late 20s, a partying lifestyle escalated into a problematic addiction.

“I had my own company in New Orleans after Katrina,” Williams says. “I smoked a little pot, ate a few pills, that kind of thing. I kind of managed it and went to work every day. I had 80 or 90 employees, made about $300,000 a year, and I’d have a little coke party every month or two. I was at a party and we were out of coke. Someone brought me a line of brown powder and that was my intro to heroin. I snorted a line of heroin and within 4 months I was an addict. For two years I didn’t run out of heroin. I ran that company all the way into the ground and lost everything.”

He confronted the truth that he needed to get sober for good. With little left to lose, Williams entered rehab, where he had a self-described spiritual experience and started feeling excited to live for the first time in years. His wife at the time, however, did not get sober, and Williams earned custody of their children, Taylor and Natalie (now grown).

As he began sharing his story at recovery meetings, Williams rediscovered that telltale knack of a natural leader – people listened to him. It was time to get back to the real world, where he could apply his strengths to the family business.

At age 35, he started his way back by laying bricks, literally, for his father at Williams Brickworks. Shortly thereafter, his dad started threatening to retire but never following through.

“He kept saying in two more years, I’m going to retire, and then two more years, and two more years,” Donnie says. “It got to a point where he felt I was taking a lot of chances and (Philip and I) were gambling his retirement.”

“Philip and I walked in and gave him $1 million. We got between $3-$4 million of property, equipment and accounts receivable. The company was strong, and my dad was set up. He said, ‘Peace, I’m out.’ He hunts and fishes and gardens. Now we don’t even talk about work.”

Bring on the boom

Since then, DRP Masonry has grown from $1 million a year to more than 15 times that.

“My Dad did a $1 million a year, and that was his biggest year,” Williams says. “When we started DRP eight years ago, we did $3 million, then $8 million, then $11 million and $14 million. Last year we did $18 million and this year we’ll do $25 million. We’ve got $70 million on the books.”

Clearly, DRP is doing something right for such staggering growth.

It’s not diversification of services. Masonry is still their bread and butter, Williams says. “All we do is masonry, commercial and military. We don’t do any residential or industrial. We’ve kept it in the direct vein of exactly what we were taught. We do about 80% new and 20% restoration. Restoration is growing unbelievably right now.”

So, what is DRP doing right? According to Williams, he starts with one purpose, and the rest takes care of itself.

“It’s this divine equation where we help other people.”

Whether it’s building sober houses, writing a book, or sharing knowledge with other mason businesses, helping people is what Williams knows best, and a natural byproduct of that mantra is that it elevates his own reputation and business.

After Williams got sober, he decided to help others do the same. He partnered with a friend from rehab and started building sober living houses. Today he has 90 beds in the Monroe area.

Once, he won a bricklayer contest at a mid-year meeting of the Mason Contractors Association of America, and not only joined the organization, but became active in it. “I just started making really good friends with the people at MCAA and got involved, and then I developed a foreman training with Tom Vacala and Jameel Irving,” he says.

He even wrote and published a book, released this year, called “Professional Masonry: Welcome to a Full Night’s Sleep,” where he shares his life story and 39 processes and procedures for how to run a successful masonry company. (Williams modestly shrugs off this accomplishment. “It’s nothing more than what everybody else does, I just put words to it,” he says. “(The book) makes it easier to train employees. It shows them, this is what we do, and this is what I need you to do.”)

As word traveled of Williams’ book, phone calls started pouring in from companies that wanted to consult, partner or even merge with DRP. The interest soon inspired Williams to start a consulting company (BRC Consulting) to counsel other masonry contractors on day-to-day operational obstacles, taking the business to scale, and succession planning.

As if Williams doesn’t sound busy enough, he also hosts a training event he calls the Masonry Movement twice a year.

“We invite leadership at DRP and I also invite my competition,” he says. “We train them, have speakers, feed them dinner and breakfast, give away tons of tools and gift cards, and teach them the same DNA to where they’re running projects and tracking projects all the same way to keep our systems and procedures intact. We’re constantly learning how to do better.”

The #2 reason for his success is relationships, Williams says – with his family, his staff and his clients.

“We do what we say, we answer the telephone, and we hire really smart management,” he says. “I like to keep people accountable. We’ve got good attorneys and good consultants. My son-in-law (Jimmy Gaiennie) has been with me for eight years and he’s one of our project executives. My son (Taylor Williams) and nephew (Dillon Williams) are both 20 and have been working in the business since they were little kids. They’re both in school for construction management. The whole next generation includes six guys in their 20s that I hired right out of college as interns.”

Always watching the fifth generation with laser focus, Williams is keen to know who will replace him one day.

“It almost feels like I’m obligated on some level to take care of all these people,” he said. “I’ve got my cousins’ kids, my kids, my nephew, and my oldest daughter, Chandler, who developed our website, and I’m just watching to see who’s going to take my spot. Who’s going to be the leader here.”

Full speed ahead

DRP Masonry shows no signs of slowing down, nor does Williams – he’s saving that for the next gen.

“My Dad used to tell me that if a man could save up half a million and have equipment paid for, he could enjoy life and do what he wanted,” Williams said. “When I saved up a million and had $1 million in property paid for, I decided to grow this thing and see how big I could make it. By the time I’m 60, I want to be worth $25 million. If I can hit $10 million, I’ll already have the momentum.”

Williams puts in the work now because he wants it to be easier for the next generation once they’re in charge.

“I would hope that they slow it down,” he says of the fifth generation. “The growth is hard because you have to invest so much time and take so many chances. My goal is to perfect and tighten up all these processes and procedures so they’re not doing as much work.”

Why does Williams feel responsible for shouldering so much of the work himself? Maybe it’s gratitude that the lesser version of his life – the one that could have been and almost was – didn’t win in the end.

That isn’t to say there aren’t still days full of frustrations and challenges.

“Whenever I feel like my family is not as bought into the work and tradition and legacy as I am, because I’m still at work and there’s nobody but me and the office manager here, I think, ‘What would my life really be like if I didn’t have them in my life?’”

![]()