PROSOCO’s story began during the post-World War II building boom, when returning U.S. GIs needed a place to live, and construction sprawled out to the suburbs. Back then, brick was one of the most common materials for cladding new homes. Brick masons couldn’t keep up with demand. The solution? Work faster.

“One of the ways you build brick faster is to make your mortar set up faster,” Boyer said. “That required masons to use higher ratios of Portland cement, which is a component of mortar that separates the brick and makes buildings resistant to weathering.”

“When you increase the ratio of Portland cement in the mortar, masons can lay up more courses of brick during a day. But being pushed for time, they were messier than ever before.”

Before the building boom, masons would typically clean their work as they went. Suddenly, that changed. Now, masons were paid to lay brick. Other trades were paid to come in afterward and clean it.

“We had faster construction, bigger messes, and higher Portland cement mortar smears than ever before in the history of the country,” Boyer said.

In the 1940s, the traditional method to remove this hardened Portland cement mortar was with a dilution of hydrochloric acid, commonly referred to as muriatic acid.

As design styles adopted a more modern aesthetic, brick producers began introducing a variety of brick colors besides red.

“They would incorporate different clay blends, metal salts, and use lower firing temperatures to produce gray, brown and lighter colors of brick,” Boyer said. “These different colors were more absorbent, more vulnerable to damage and discoloration from muriatic acid than traditional red bricks.”

“You put muriatic acid on a gray brick, and it may turn bright green. A white brick may turn yellow, green, orange or purple.”

Other standard methods at the time to clean brick included sandblasting and chip hammers, which had potential to cause even more damage. AJ Boyer and his sons, Jerry and Ken, believed there had to be a better way.

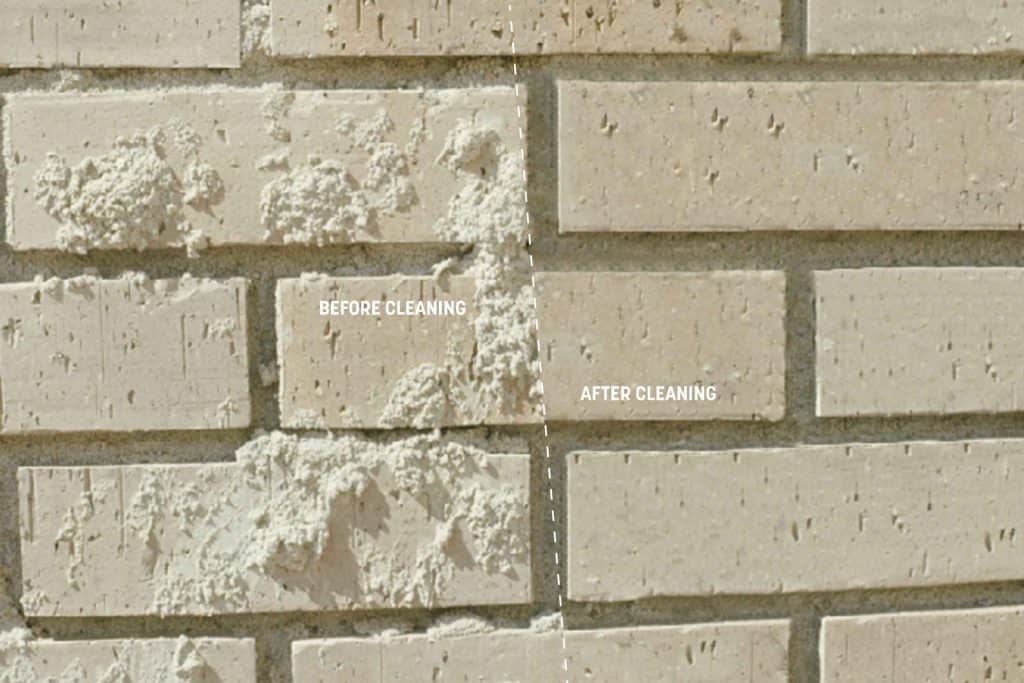

PROSOCO’s response was to use a buffered acid solution it had originally commercialized to descale metallic cooling systems on cars. When coupled with antioxidants to protect the metallic salts used to impart color in brick, the new solution was successful in removing hardened Portland cement mortar smears without causing discoloration.

“An idea was born,” Boyer said. “My father, Jerry Boyer began developing highly specialized formulations expressly for the controlled removal of excess mortar from new brick.”

That philosophy, born in the 1940s, is the same approach PROSOCO employs today for research and development: assessing a need, identifying what could cause harm, and eliminating potential for harm while still achieving desirable results.

Where new needs arise, PROSOCO has consistently been the first to respond to make new, specialized products the right way.

While continuing to refine its line of brick cleaners in the 1950s, PROSOCO was the first to use food-grade acids.

“Many of the industrial muriatic acids were reclaimed products that had impurities of their own,” Boyer said. “Those impurities would impart unwanted color to the newly cleaned brick work. That prompted us to start using ‘virgin’ acid to eliminate the potential adverse effects.’”

It was around this time that PROSOCO adopted its long-standing mission of creating purpose-built products. While other companies would market alterations of one formulation to serve multiple purposes, PROSOCO customized the right chemistries in dozens of different formulations tailored to address specific substrates, surface deposits, subsurface stains and other variables.

“Our first purpose-built, new masonry cleaner was 101 Lime Solvent. While that formulation has been improved many times since its introduction in the 1940s, it remains a specialty cleaner designed to remove hardened Portland cement mortar from new red brick,” Boyer said.

“For light-colored brick, we introduced 600 Detergent in 1956. Shortly thereafter came Vana Trol for brick that’s prone to vanadium staining. Then came a line of even more specialized stain removers – Ferrous Stain Remover for rust stains, 800 Stain Remover for vanadium and manganese staining, and White Scum Remover for tenacious surface and subsurface staining caused by residues of Portland cement. Prior to these products, the notion of proprietary cleaners for newly erected masonry was unknown. That was the first industry that Process Solvent pioneered.”

In the 1960s, 70s and 80s, architectural concrete masonry units (CMU) came onto the scene. In this case, the challenge was to remove excess Portland cement mortar from masonry units based on Portland cement. How do you isolate one from the other?

“It requires a better understanding of the different wetting characteristics of excess mortar smears versus the cured concrete block. That challenge gave birth to a series of new formulations tailored to the specific demands of cleaning new masonry constructed with colored, architectural CMU.”

Natural stone, often used alongside clay brick or CMU, presented another cleaning challenge.

“Each natural stone is its own animal,” Boyer said. “Understanding the chemical sensitivity of each stone type, eliminating what may do harm and focusing on what benefits you can impart with proper wetting and proper rinsing characteristics at the lowest possible chemical concentration, gave birth to other cleaners.”

What about manufactured stone, which Boyer calls the “wild west” in terms of chemical vulnerability. How do you clean unwanted stains from this substrate without removing applied coloring?

“With thin manufactured stone veneers, the first test of vulnerability we do on samples submitted to PROSOCO’s laboratory uses a baby wipe to see how much of the coloring comes off. It should be one of the most controlled, gentle cleansers you could use. The one you use on your babies.

Many manufactured stones, more than the industry may care to hear, are vulnerable to removing color with a baby wipe. How do you clean that in a construction setting? It’s challenging. That’s the kind of approach we take to developing different cleaners for different substrates.”

![]()