A restoration team looked far and wide to match plaster from historic adobe.

In southern Arizona, dotting the literal U.S.-Mexico border, is Camp Naco -- a vestige of American history that a group of passionate individuals has worked to not only preserve but also resurrect as a functional and educational tribute to its past.

In 1911, Camp Naco began humbly as a tent camp to house African American Buffalo Soldiers from the 9th and 10th cavalry regiments, and later the 25th infantry regiment through 1923.

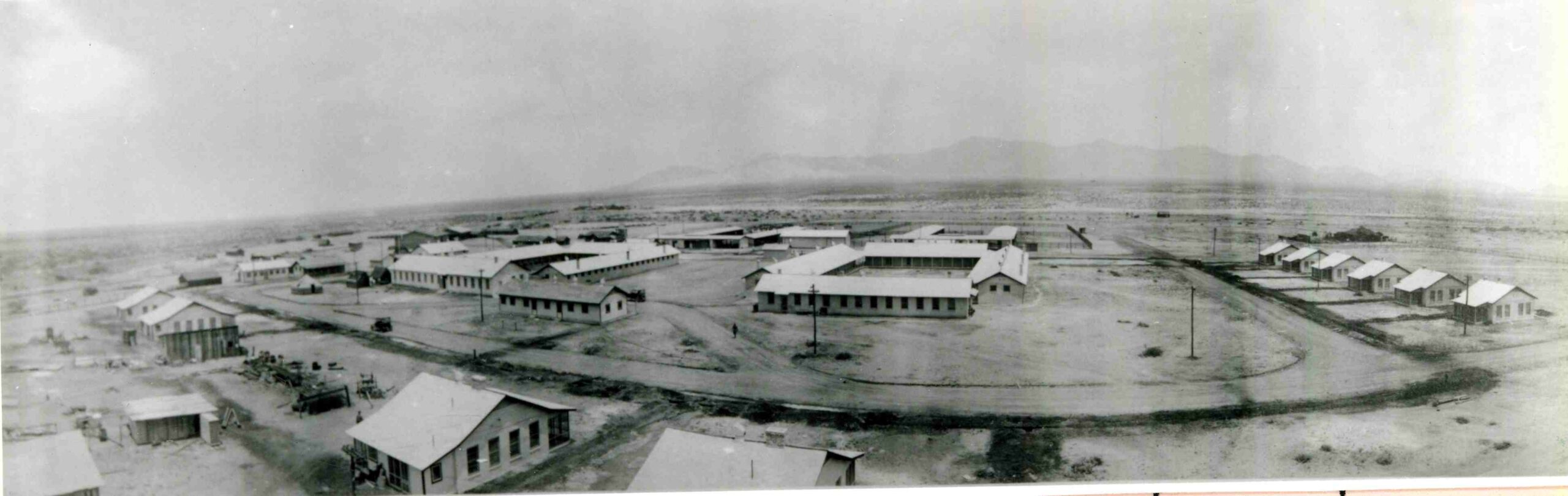

Eight years later in 1919, a permanent encampment of 22 adobe buildings went up, and stayed up -- this complex is the only surviving post from the original 35 permanent camps along the border to protect incursions from the Mexican Revolution.

In 1937, the complex reverted to private ownership and remained that way for nearly 70 years.

Over the last 20 years or so, several factors have combined to save the property, including the formation in 2008 of the Naco Heritage Alliance, a 501(c) (3) organization aimed exclusively at preserving the property’s historic adobe buildings.

An important milestone occurred in 2012, when Camp Naco gained a listing on the National Register of Historic Places. The 16-acre property was acquired by the city of Bisbee, Ariz., in 2018; in 2022, it was listed on the 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list by the National Trust for Historic Preservation; and $8.1 million in grant money was awarded that same year to the Naco Heritage Alliance and City of Bisbee (from the Office of Arizona’s Governor and the Mellon Foundation). Combined, these developments have propelled the site toward rehabilitation as well as the development of community programming to sustain its use.

A tough match

According to Mike Normand, Construction Project Manager for the City of Bisbee, Ariz., a primary reason Camp Naco is still standing is what it’s made of.

“It was one of two (camps) constructed of adobe block, and we’re told that the adobe may have come from high clay content soil on the site,” he says. “The buildings have been vacant for decades. A group of volunteers were doing their best to maintain and preserve it. Over time, some of the buildings collapsed. Some were lost to fire. There are about 20 adobe buildings left that we’re trying to restore. One of the issues was the plaster.”

“We needed a recipe so we could reverse-engineer the plaster and duplicate it.”

In several places, areas of the adobe buildings’ exteriors, the plaster, which had been used to protect the adobe blocks as a coating, was in bad need of repair. To restore the plaster exteriors, Normand spearheaded a geological investigation.

“The plaster seemed to be unique,” Normand says. “We began trying to go back to the Army Corps of Engineers in 1919 to try to figure out the building typologies, the materials, who made those decisions and where did the materials come from?”

Normand contacted several labs in Arizona with few promising results.

“We were trying to find a lab that could break down the sample of the plaster and tell us what the components were,” he says. “We needed a recipe so we could reverse-engineer the plaster and duplicate it.”

“I called several labs here in Arizona and talked to other adobe specialists. They said, ‘Oh, we don’t do that, but call this lab,’ and then they said, ‘No, we don’t do that type of testing.’ I was following all these leads, at labs not only in Arizona but all over the country. I finally was recommended to contact Courtney (Murdock) at AMT Labs, and she said, ‘Yes, we can do that.’”

Murdock, Director of Project Testing for AMT Labs, says each sample she receives for testing tells a unique story, but Camp Naco is one that stood out to her.

“I always love to hear the stories behind the samples that we are sent for evaluation, whether that is a petrographic analysis as in the case of Camp Naco, or one of our many other specialized tests like mortar analysis, cleaning, or consolidation,” she says. “Camp Naco’s history and revitalization were particularly fascinating to me, and we were honored to help the project team match the original plaster on these adobe buildings.”

With the results from AMT Labs’ petrographic analysis of the plaster, the Camp Naco team was ready to move forward.

“It was very helpful,” Normand says. “Now we have the recipe for the plaster for the architecture team. That’s where we are right now. We’re bringing on a contractor, and in the next few months, we’ll start the rehabilitation around the end of this year.”

A recipe to rebuild

With the results of the petrographic analysis from AMT Labs, the project team could move forward with the recipe to repair the plaster, which ended up being lime-based in composition. Normand said for its 100-year-old age, it held up remarkably well. “Ninety percent of the coverage was in good condition,” he says.

"We are beholden to standards of preservation, so (the plaster) needs to be matched to the highest degree possible of what was existing there."

The importance of repairing the plaster material with as close of a match as possible to the original was taken very seriously by the Camp Naco team.

“We are beholden to standards of preservation, so this needs to be matched to the highest degree possible of what was existing there,” says Brooks Jeffery, who was hired by the City of Bisbee as a strategic planning consultant to launch construction and community programming initiatives on the site.

“These buildings have survived and are thriving because of the protective coat that the plaster provided, so we want to replicate the recipe, but also take a scholarly kind of approach to talk about how we find the materials and do the investigative research.”

Of course, the plaster is only one component of the entire restoration effort at Camp Naco – an undertaking which is expected to be completed around 2026.

“There are some buildings where, before the roofs were repaired, water got into the building and eroded portions of the adobe walls,” Jeffery says. “There will be some reconstructing of some sections of the walls, and then there are seven structures that burned, and those will need to be rebuilt. Our plan is to have some workshops on site that can provide education and training about using adobe for construction. We’ll probably be making adobes on site from the materials native to this site. The soil here is very high in clay content and sand aggregate, which is ideal for mixing and making adobe blocks.”

Twenty adobe buildings will ultimately be restored to provide a variety of services and purposes for the underserved border community of Naco. One of the buildings, which was originally a hospital, will be an interpretive center about the history of Buffalo Soldiers. One will be a community center and library. The barracks buildings will be rehabbed into classrooms, workshops, and art studios, and open spaces that were previously parade grounds will be repurposed into outdoor venues. Former officers’ quarters will serve as housing for a caretaker, artists-in-residence, and local workforce.

“The Bisbee area is known for its heritage tourism with a thriving arts scene and a great community spirit,” Jeffery says. “That helped inform the three pillars to our vision for Camp Naco: 1) to honor the legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers in the American Southwest; 2) to advance the diverse arts, culture, and history of the Arizona Borderlands; and 3) to serve the community of Naco, Arizona.”

![]()