At the beginning of 2025, a project team cleaned the historic New Orleans Lakefront Terminal Building just in time for it to welcome private jets full of Super Bowl LIX attendees.

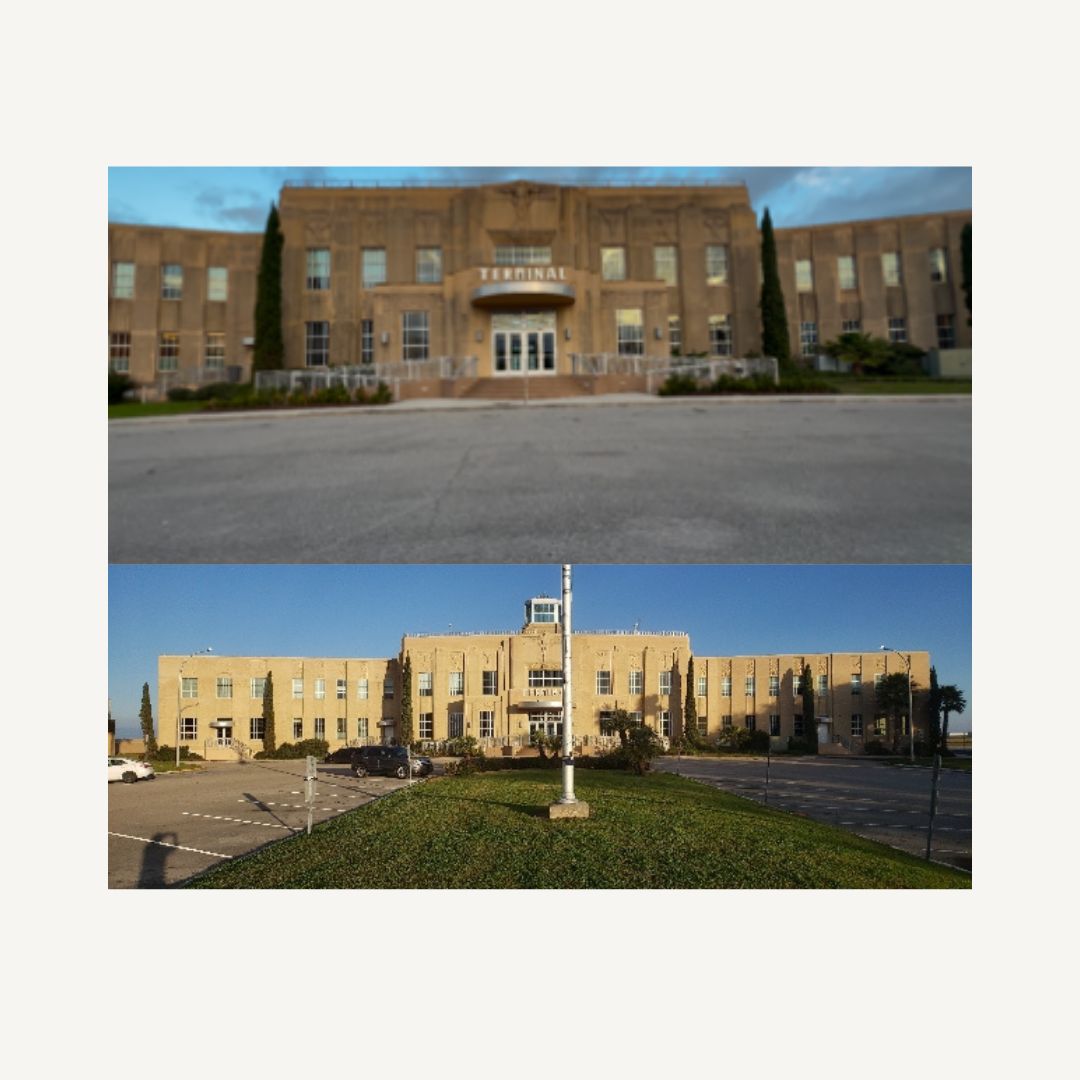

When it opened in 1934, Shushan Airport was much more than an airport. Touted at the time as the largest and most modern terminal building in the entire country, and located about 5 miles northeast of downtown New Orleans, the Art Deco building contained all sorts of amenities and attractions unheard of for a facility of its type. (By comparison, its counterpart in Atlanta at the time was a little house and a strip of dirt.)

Built under the order of then-Louisiana-governor Huey Long, and named for Long’s friend Abe Shushan, the airport originally served New Orleans as its main airline airport, and it also contained a surgical suite with exam rooms, a post office, private sleeping quarters with baths, a commercial kitchen, a café, and offices for the Departments of Agriculture and Commerce.

Despite its location outside of the city, the airport gained a reputation amongst youth as being the place to be seen. Young people in this era were known to skip the myriad speakeasys downtown in favor of driving out to the airport in “the middle of nowhere.”

“It was sort of a big secret to walk from the street into that building because people didn’t realize the magnitude of the interior of the building, the décor, and who was there,” said James Fitzmorris Jr., former Lt. Governor of Louisiana, in a video about the restoration. “You really felt like you were going someplace special.”

Custom details everywhere

In order for a place to feel special, it really needs to be special, and the Shushan Airport was, inside and out. Every element featured exquisite detail, from the terrazzo floors and plaster to the brick and stucco, and nearly everything was installed by masters of their craft.

The building’s exterior is composed of a material not commonly found on buildings today.

“It’s like a Portland cement mixed with quartz aggregates,” said Paul Dimitrios, architect with Richard C. Lambert Consultants, who led both its 2013 and 2025 restorations. “They parged it on the building’s speed tiles and then came back and rubbed out the cement on the surface to expose the quartz aggregates so they’re visible. It’s like a concrete surface, but it’s very different from what you would normally see because of the finishing techniques they used. Everything about this building was special and done to the highest standards."

A handful of buildings in the region designed by the airport’s architect, Leon C. Weiss, feature many of the same type of ornate panels and iconography that are unique to the airport’s exterior, including the Louisiana state capitol building and charity hospital in New Orleans, Dimitrios added.

In 1946, Shushan gave up its function as a commercial airline airport to the new (and much-larger) Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport, but the smaller airport would continue to serve Learjets and other private planes. By then, it had changed its name to the New Orleans Lakefront Airport Terminal.

Few could have predicted the ominous changes the terminal would soon face.

In the 1960s, under the fear of a Cold War, the building was entirely encased in metal to convert it into a nuclear bomb shelter. It remained that way until 2005, when Hurricane Katrina flooded the exterior airfield with 8 feet of water, and the terminal’s interior took in 4 feet of standing water. Luckily, officials determined that the building could be savaged.

Dimitrios and his firm, Richard C. Lambert Consultants, operated with a mission of preserving as much of the building’s original character as possible.

“It was a Herculean effort what Paul and his team did back in 2013,” said Todd Borges, owner of Calypso Painting, the contractor on the job. “He had to go far and wide, all over the world, to find the craftsmen to bring it back to the original. Paul hired them all.”

A Super-speedy timeline

Fast-forward to 2025, 12 years after its last major restoration. As New Orleans prepared to host Super Bowl LIX, the building couldn’t hide the fact that it had become dirty again.

“You’ve got the lake, the salt water, the atmospheric staining from the jets, and the fact that we get 70-80% humidity practically year-round,” said Dimitrios. “There’s algae on every building we have in Louisiana. It’s an ongoing problem.”

The decision was clear: the building needed cleaning, but the project team was up against two foreseen obstacles: 1) cold weather; and 2) the fast-approaching deadline of the Super Bowl on Feb. 9, 2025. Of course, airport officials wanted the building in pristine condition for all the Super Bowl attendees descending into the city on their private jets.

A last-minute decision by the chief engineer of the Lakefront Management Authority, Laith Al Shamaileh, Ph.D., made a quick turn-around possible. He split the scope of work into two separate contracts: one for pressure-washing and another later for crack repair and sealing. "This approach reduced the overall dollar amount of the project, allowing us to award it without triggering the more extensive legal steps required for larger projects," Al Shamaileh said.

With the help of Bob Holmes of HolmesCo Inc., an independent PROSOCO rep serving Louisiana, the design team connected with contractor Todd Borges of Calypso Painting – a connection for which Dimitrios says he’s extremely thankful.

“Todd was very meticulous,” Dimitrios said. “He called me every day about what was going on, and he was really conscientious about doing the best job he could. Had we not had someone of his caliber, we wouldn’t have gotten the results that we did. He brought that building back to what it was the day I finished it back in 2011.”

With the clock ticking closer and closer to kickoff, Borges arrived on site and test panels with Holmes commenced. Three or four different cleaners were tested on the cement quartz, and two winners were determined: 2010 All Surface Cleaner would be used on the majority of the building’s exterior, while SafRestorer was the winner for areas with more severe water and algae staining.

A big advantage of 2010 All Surface Cleaner is that it’s safe on metal and glass, so no taping was required of windows or adjacent aluminum features on the building before applying the cleaner.

Holmes recommended 2010 because it performed just as well as the other cleaners tested. “I knew it wouldn’t slow them down because they wouldn’t have to board up windows that another chemical would have required to protect the metal frames and glazing on the glass,” he said. “It worked really well on the atmospheric staining.”

Borges began his cleaning process with a 4:1 ratio of cold water-to-2010 for a majority of the substrate; and a 5:1 ratio of cold-water-to-SafRestorer to spot-clean the stubbornest stains. Then he tried a 4:1 ratio for SafRestorer.

“Three-to-one didn’t do much better, so we went back to 4:1 so we could be as efficient as possible with the product,” Borges said.

The cleaning was going well until the temperatures dropped significantly, and Borges started seeing less-than-desirable results.

“Unfortunately, it was very cold weather, about 33 degrees,” Borges said. “It was a high of 36 in the afternoon for a week or two.” He called Dimitrios and asked if he could start using hot water instead of cold water to dilute the cleaners. With the owner’s permission and a change order made, Borges began using 185-degree water for applications of both products, much to everyone’s satisfaction.

“The hot water made a big difference,” Dimitrios said. “Had we been doing it in the middle of the summer, it wouldn’t have been an issue. The products that we used were certainly part of the reason why we got the end result we did.”

“Once we got everything dialed in, the system worked very efficiently,” Borges added. “A combination of 2010 and hot water was a great recipe and it worked great on the pollution.”

Despite a few unforeseen setbacks (the Jan. 1 terrorist attack in the French Quarter meant lots of military aircraft obstructed access to the tarmac side of the terminal), the project was successfully completed in time for the Super Bowl (and all the attendees flying in by private jet).

Even more than the victory of meeting their tight deadline, Borges said his greatest gratification is playing a part in bringing the historic building back to its original beauty.

“When Hurricane Katrina came in and left 8 feet of water, all this beautiful artwork and design details were sandwiched in there behind the old metal cladding,” Borges said. “It was just remarkable how they found people with the skillset to restore each detail.”

“To be able to come in and clean it was a nice job to have, but it was exciting because a building like this is rare. The building is stunning. It was a privilege to be part of the beauty they restored.”

![]()