Daniel Levy acknowledges the adoption of autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) is lagging in the U.S. But that’s not stopping him from using it to build Passive House-certified homes.

Years ago, Levy taught woodworking technology at the University of Maryland and calls himself a “teacher at heart,” but he’s also a lifelong student of building materials and science. Today, he’s the owner of Greenspring Building, a Passive House-certified builder and consultant in Hillsdale, N.Y.

His first Passive House build in Woodstock, N.Y., includes a 2,400-square-foot main house plus a 500-square-foot apartment that he intended to rent out as a short-term rental. Instead, Levy ended up with a long-term tenant who has chemical sensitivities; it met her need for an apartment with healthy indoor air quality.

This time, he’s building in Hillsdale, N.Y., where Levy was able to buy property zoned mixed-use in the center of town. “It’s 20 minutes to Great Barrington, Massachusetts, an hour to Albany, and 20 minutes to Hudson. A lot of New Yorkers have getaway homes here. Then with Covid, some gave up their New York apartments and came to their getaway homes permanently.”

Levy’s first project on the site is a duplex, which can also serve as a model for row homes. He intends to live in the first unit, and the second smaller unit will be a short-term rental. “It's one thing to build a net-zero-energy building, yet I’ve realized few have experienced a truly comfortable home. This is an opportunity for others to learn about this construction and experience the comfort and healthy aspects of an AAC Passive House.”

What is AAC?

The more interesting part of Levy’s duplex is not the location but what it’s made of. Autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC), Levy says, can be handled like wood but offers several advantages over timber.

“To make AAC, they put any type of sand (and even recycled AAC and concrete) into a ball mill, where it gets ground up into powder,” Levy says. “It’s then put into molds and blended with water, lime, cement, and a trace of aluminum. A chemical reaction creates hydrogen, which makes the ‘cake’ rise, then it starts curing. They run it past piano wires to slice it, then it goes into large-scale autoclaves which speeds the curing.”

What are the advantages of AAC? Levy could talk about them all day.

“This is masonry that’s 75% to 80% air—so it is thermal and acoustic insulation, and it outperforms concrete in fire,” he says. “Large aggregate in concrete expands and cracks concrete, so after a fire, you have to repair or replace concrete. With the fires in California and Colorado, even some concrete slabs failed. You would never think of concrete failing in a fire. AAC doesn’t, because in addition to containing no large aggregate, its open pores means there’s a place for steam to go without blowing the product apart. In most uses, AAC has a 4-hour fire rating, which is higher than concrete. What I have heard is that the fire test was actually run for 8 hours, and it was pointless to keep going because building codes do not require that high a rating. Yet, you cut it like wood with woodworking tools. You can drive nails and screws into it. And despite the high air content, the air bubbles aren’t connected, so there’s no air leakage.”

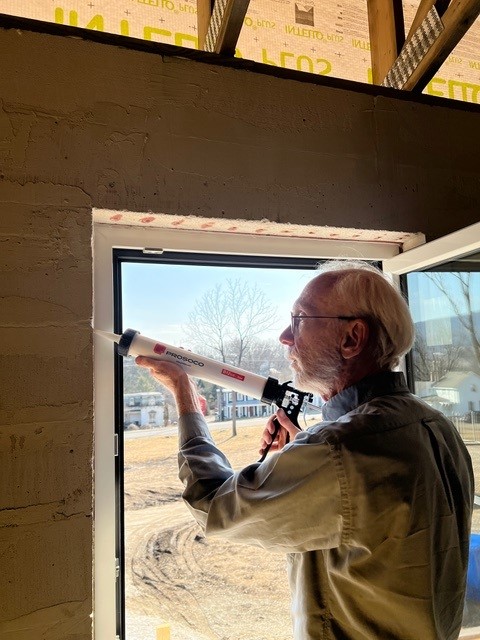

For this reason, Levy doesn’t use a primary air barrier. He says AAC is all the barrier he needs for the field of the walls. However, for the rough openings (his duplex features 23 windows and 3 doors), he is using FastFlash around the openings and AirDam to seal the window frames. He also uses PROSOCO Adhesive to bond lumber as needed, along with mechanical fasteners.

Watch a real-world application of PROSOCO Adhesive

“Most build residences with a wood frame,” he says. “With AAC, I’m going to run plaster to the reveal and window frame, do the same thing on the outside with lightweight stucco on Rockwool Comfortboard, wrap it around, and then caulk that joint. It’s so simple. There’s no wood movement, and nothing that’s going to rot.”

Levy isn’t alone in his advocacy for AAC. PROSOCO CEO David Boyer joins him in his enthusiasm.

“Though AAC is a bit esoteric, it’s a brilliant way to build and produces some of the most serene, healthy living conditions you’ll ever experience,” Boyer says. “It creates a robust, vapor-permeable, insulated barrier wall assembly that does not require a separate air barrier.”

How is that, exactly? “Every type of insulation is nothing more than trapped air in a different wrapper,” Boyer says. “AAC traps bubbles of air through the depth of the wall, wrapped in concrete. AAC’s inherent aversion to cracking creates its own inherent air barrier. Dan has opted to protect the rough openings to avoid any potential for the transfer and accumulation of liquid water beneath window, door, and other items that extend through the wall mass.”

Despite a long history in Europe and many proven benefits, AAC is still not readily used in the United States, a fact that Levy hopes will change.

“It’s actually a really old product, and it’s tested and certified all over the world,” Levy says. “There was an article a few years ago that said about 60% of German construction and 40% of English construction is built with AAC. It just had its 100th anniversary in Sweden. A Swedish researcher was trying to create a masonry product that would be as easy to use as wood. But because of wood’s tendency to burn, rot, get eaten by termites or insects, and support mold, they wanted to build out of something more durable. He put the samples into an instrument autoclave and that was the eureka moment that this works.”

“It cures rapidly by putting it in a chamber with low-pressure steam. It was patented in 1924. The first manufacturer had a cumbersome name which was soon shortened to Ytong: Y is the first letter of the location, and tong is Swedish for concrete. Ytong is now owned by a German conglomerate called Xella, and there are many other manufacturers worldwide.”

Why is it not more common stateside? Levy says it’s simple lack of awareness combined with the age-old challenge of doing something differently. “American masons don’t like it because it’s too different.”

On the matter of cost, Levy believes AAC is more affordable in the long-term.

“I think it’s cheaper, particularly if you look at maintenance and utility bills,” he says. “I don’t think you can build a building less expensively, because you’ve largely eliminated maintenance. A wood building is forcing a lifetime of maintenance.”

See more photos of Levy’s Passive House in Woodstock, N.Y.

Learn more about Greenspring Building

![]()

Watch: How to install AirDam