By Guy Long and Paul Grahovac

The Master Specification of the Air Barrier Association of America (ABAA) provides: “Perform the air leakage test and water penetration test of mock-up after installation of all fasteners for cladding and trim.”

Unfortunately, ABAA and its manufacturer, specifier, consultant and contractor members have found that what happens with the fasteners in a mock-up is often not the same as what happens in the overall project.

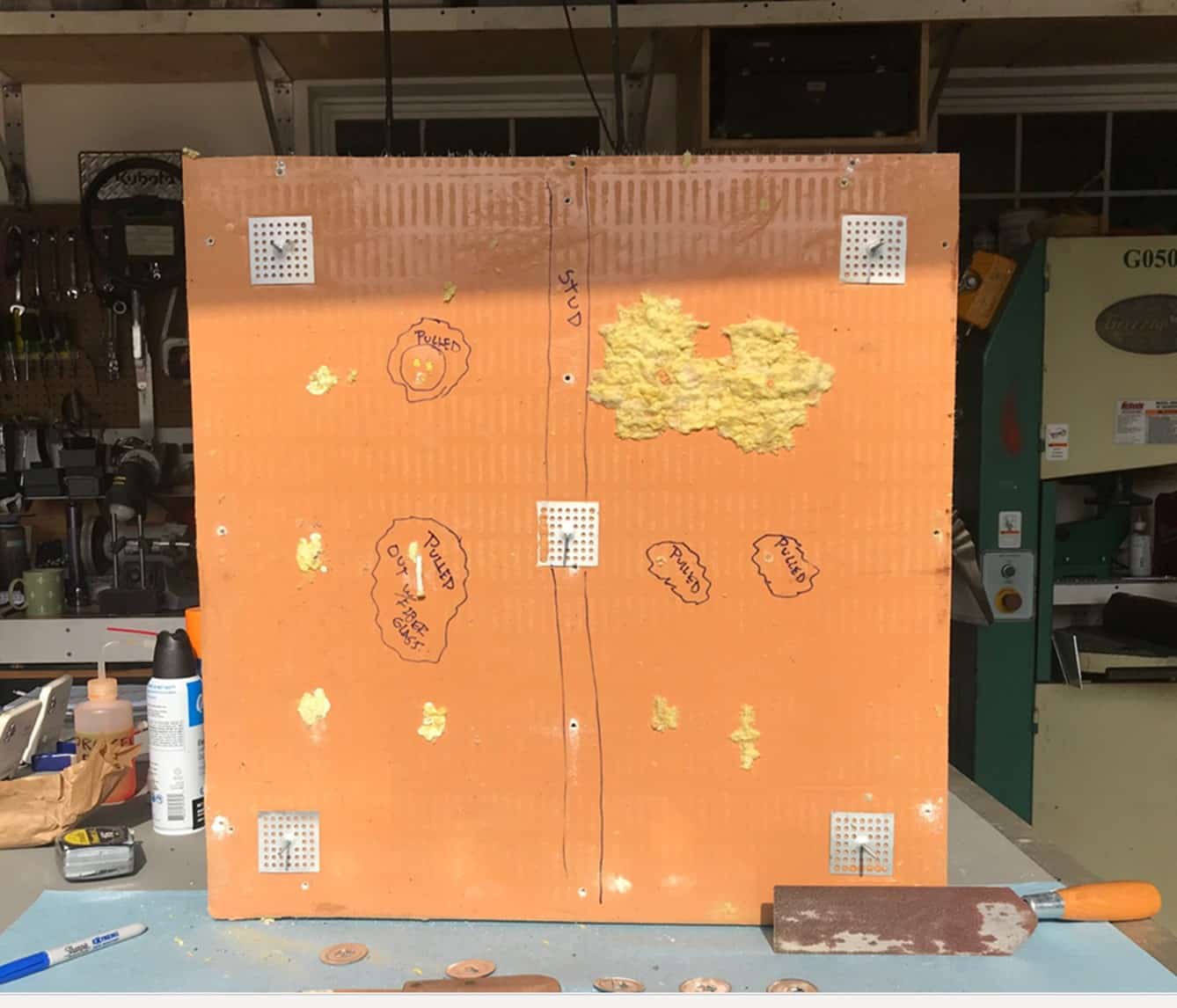

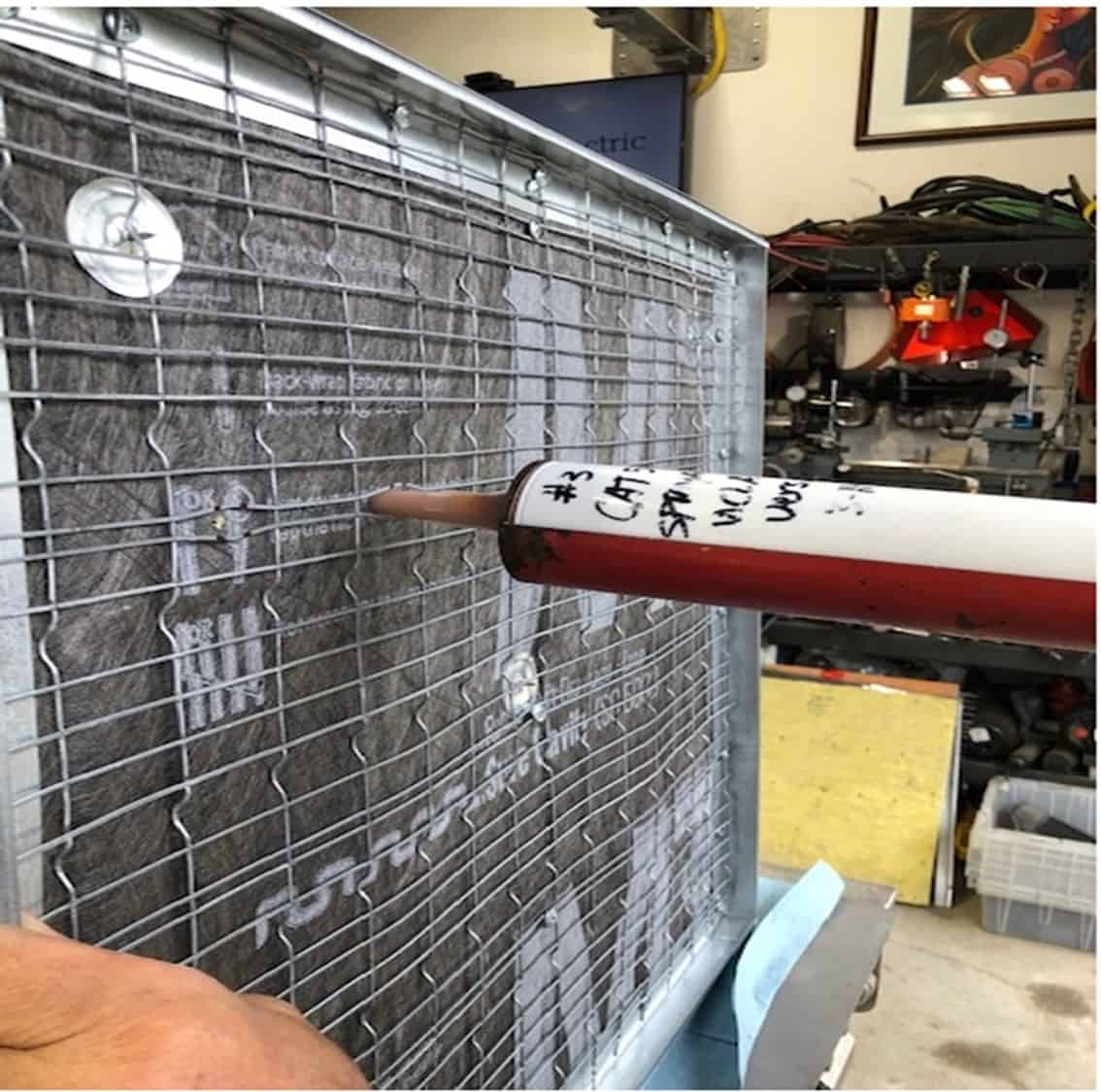

That’s why an ABAA newsletter reported on a joint ABAA and U. S. Department of Energy research project where six rows of fasteners were installed into exterior gypsum sheathing after an air and water-resistive barrier system had been installed, and the specimen was then subjected to a pressure differential and sprayed with water. Each row of fasteners was installed differently – including missed stud with fastener left in place and missed stud with fastener removed.

The results of the testing are not yet available, yet the industry continues to experience the problem -- and a need for a solution.

In 2014, building enclosure consultant Karl A. Schaack, RRC, PE, wrote an article titled, “Fasteners and Self-Sealability of Weather-Resistive Barriers” in INTERFACE, The Technical Journal of the International Institute of Building Enclosure Consultants.

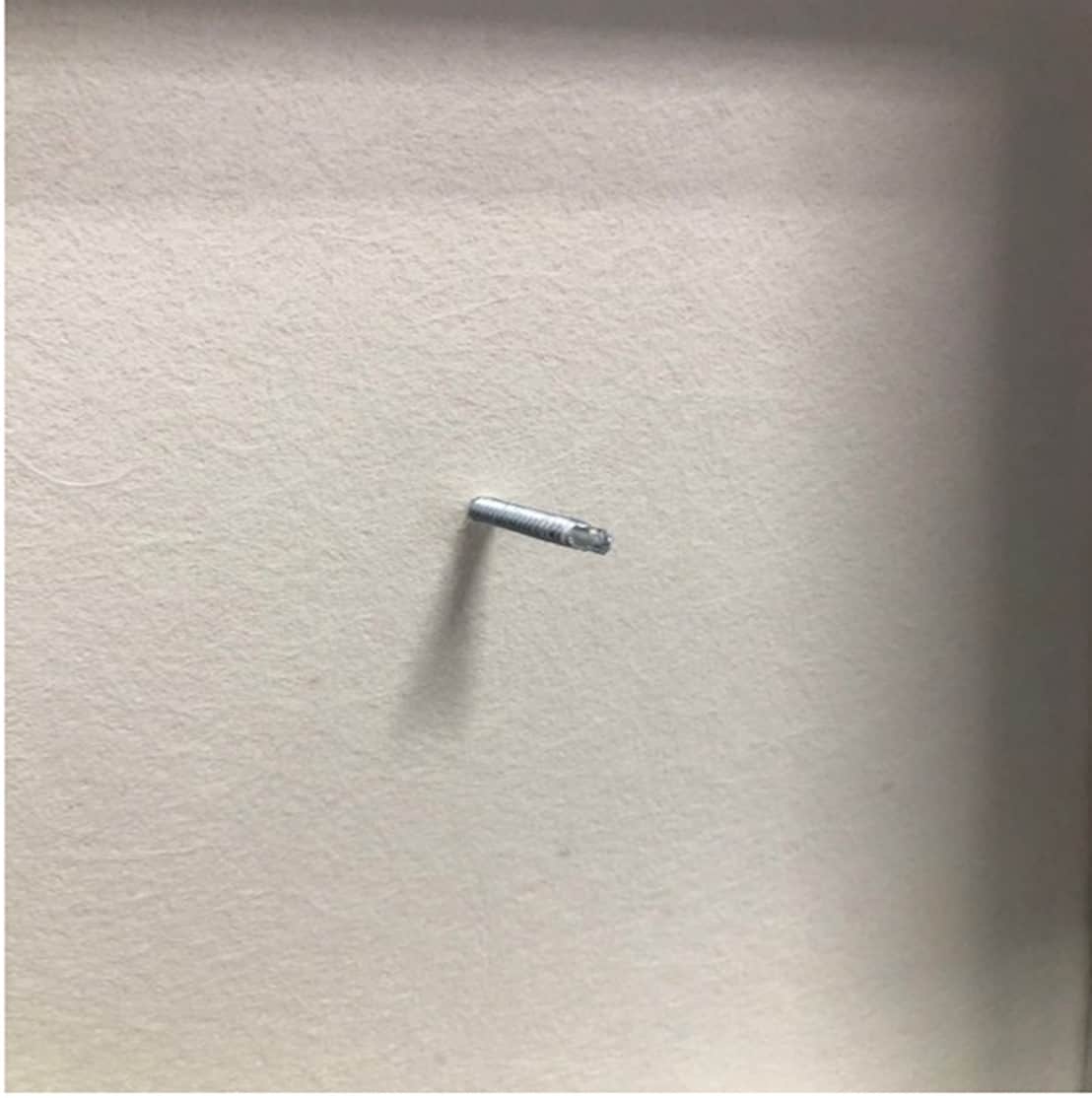

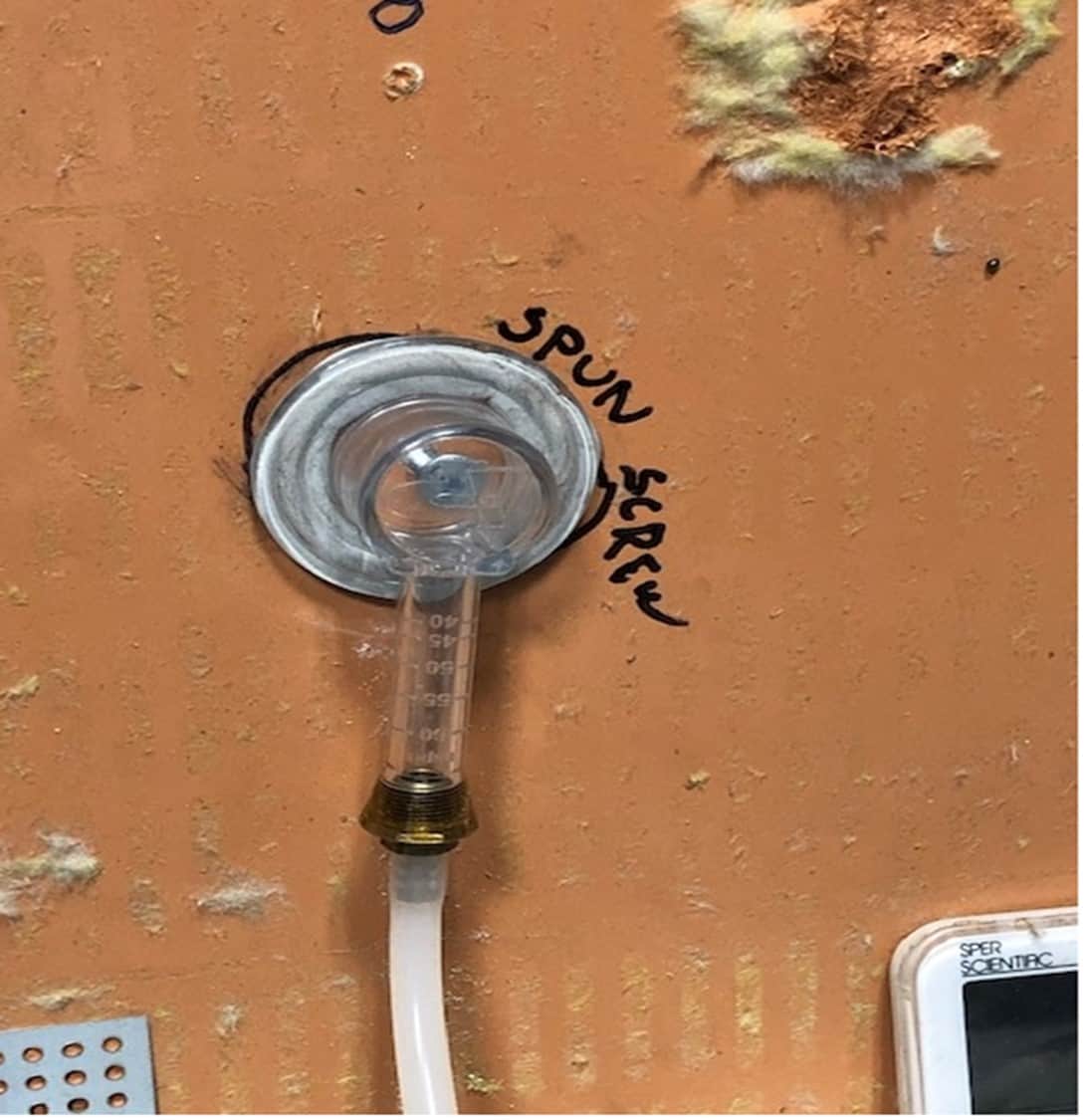

He writes: “Unlike securement into a plywood substrate that has historically been used in exterior wall construction (particularly for plaster applications), when a fastener is installed into and through gypsum sheathing that does not penetrate into a sound substrate, the fastener continues to spin, reaming out the hole. The density of gypsum sheathing is not substantial enough to allow the fastener to “bite” and attain adequate compression against the WRB material (either liquid-applied or self-adhering sheets); consequently, the fastener hole becomes enlarged as the fastener spins. With a plywood backup, a fastener could be placed in almost any location to achieve adequate compression, even though it may not penetrate into a framing member. In addition, variabilities introduced during field installation of fasteners can create conditions that result in inadequate application. For example, if the fastener or other element is not installed straight and true or is installed over-aggressively, the WRB can be damaged, which can result in water leakage, even if the fastener is driven into a framing member.

Damage to the WRB may also occur due to poorly installed fasteners, removed fasteners, or fastener length for attachment of cladding components exceeding the depth of the sub-framing member (i.e., hat channel). When light-gauge steel framing, sub-girts, hats, and masonry ties are installed on top of the WRB, and fasteners are secured into the backup structure, the rigid steel sub-framing or steel tie typically cannot conform to uneven areas in the substrate, and the fastener cannot develop full compression against the WRB to achieve an adequate seal (Photo 5).

Some manufacturers of liquid-applied WRBs recommend installation of cut strips of self-adhering sheet between the steel girt or tie and the WRB to aid in achieving an adequate seal at fastener penetrations (Diagram 2).

Additionally, the heads of fasteners may need to be treated with a dollop of compatible sealant or trowelable version of the liquid membrane to provide a more suitable seal (Diagram 3 and Photo 6). Another practice could include setting the masonry tie in “wet” liquid-applied WRB when securing to the substrate."

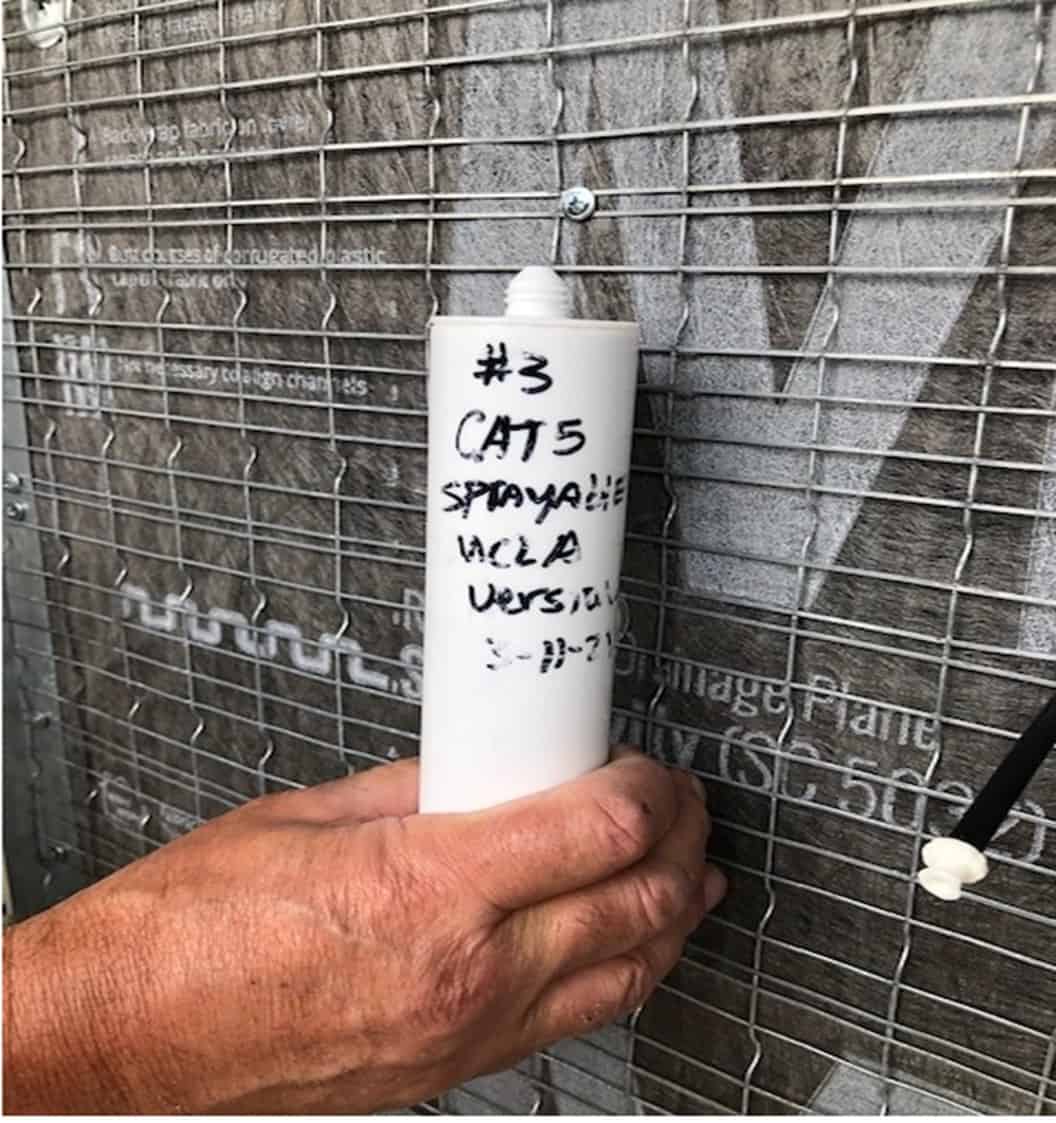

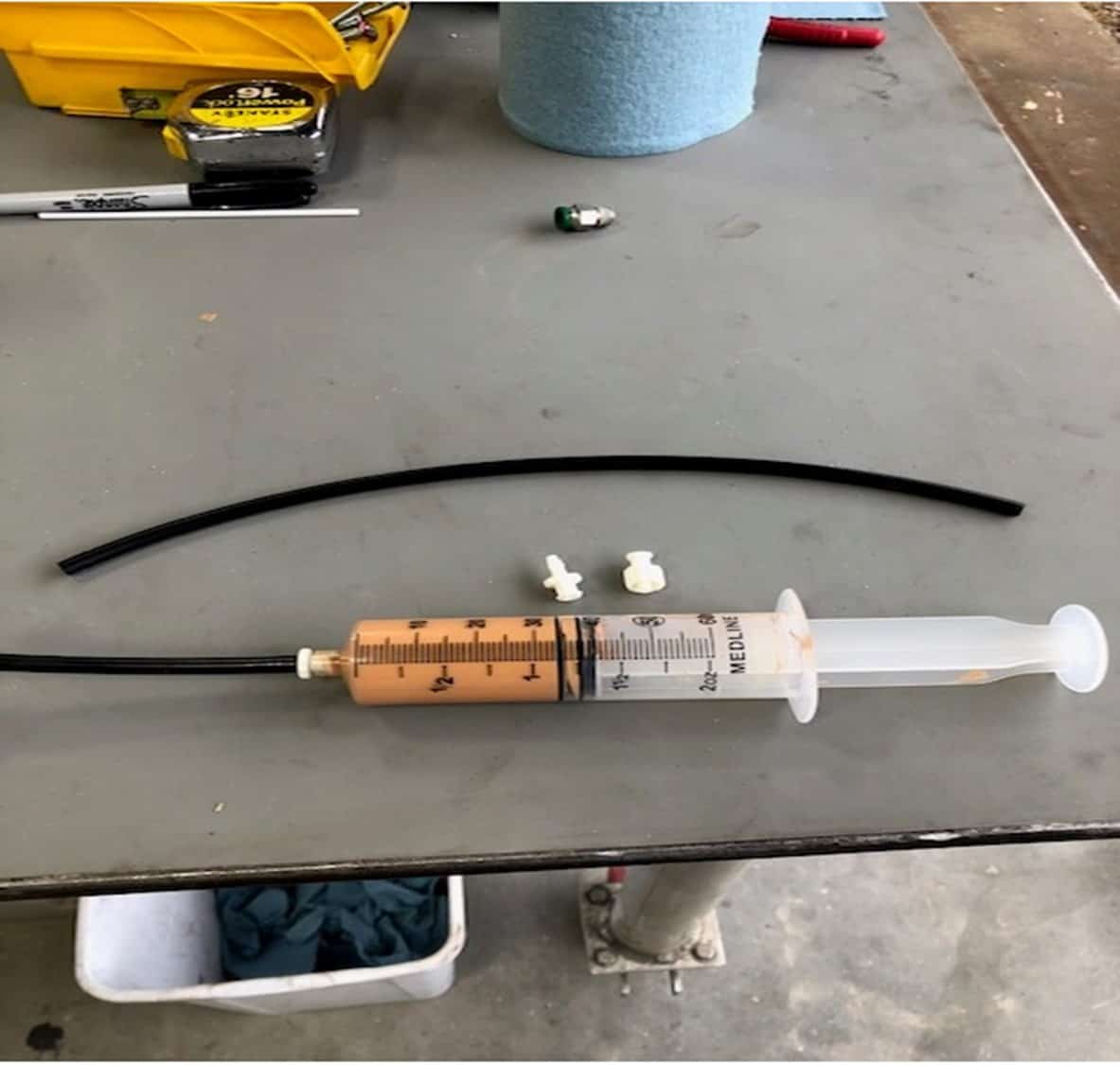

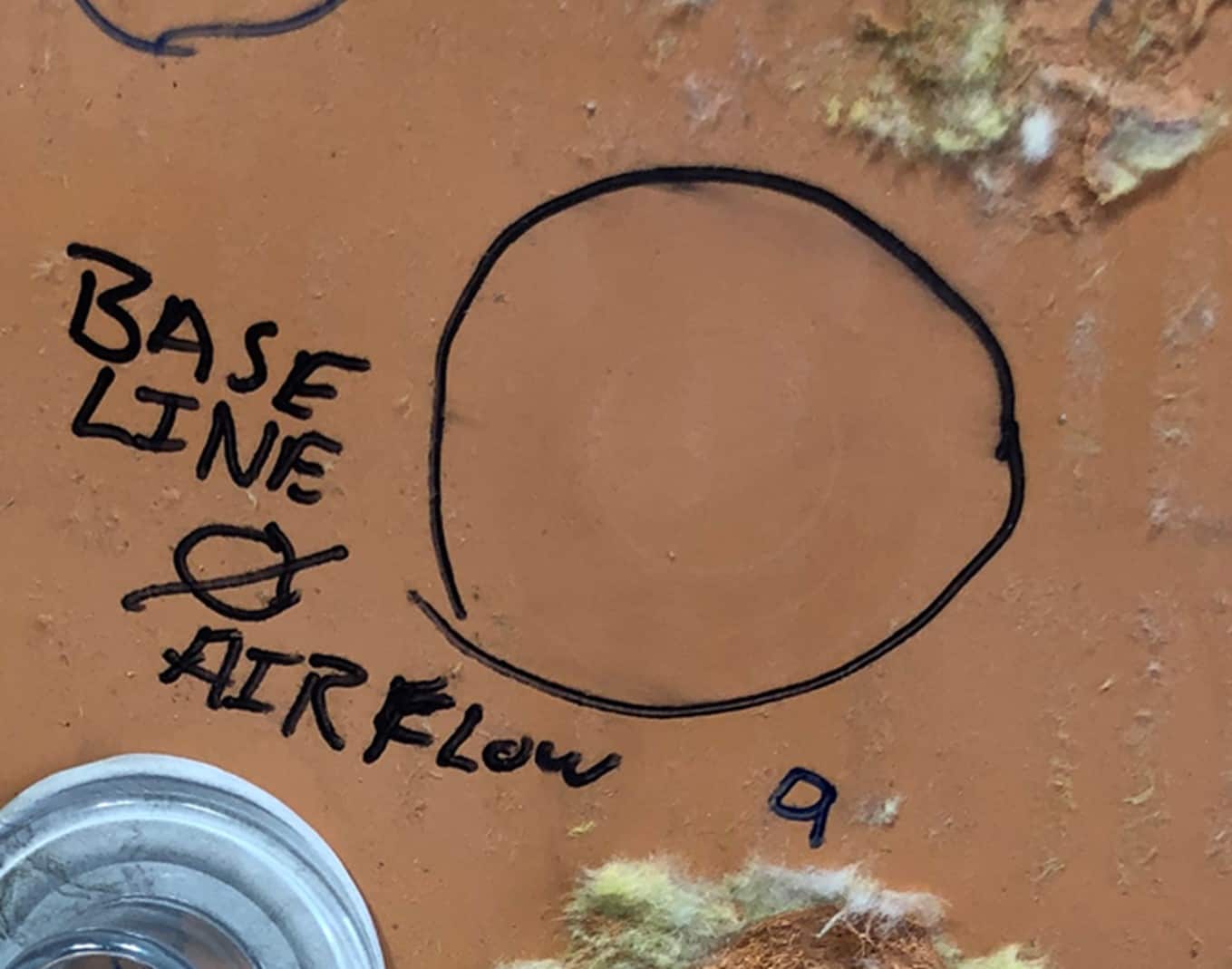

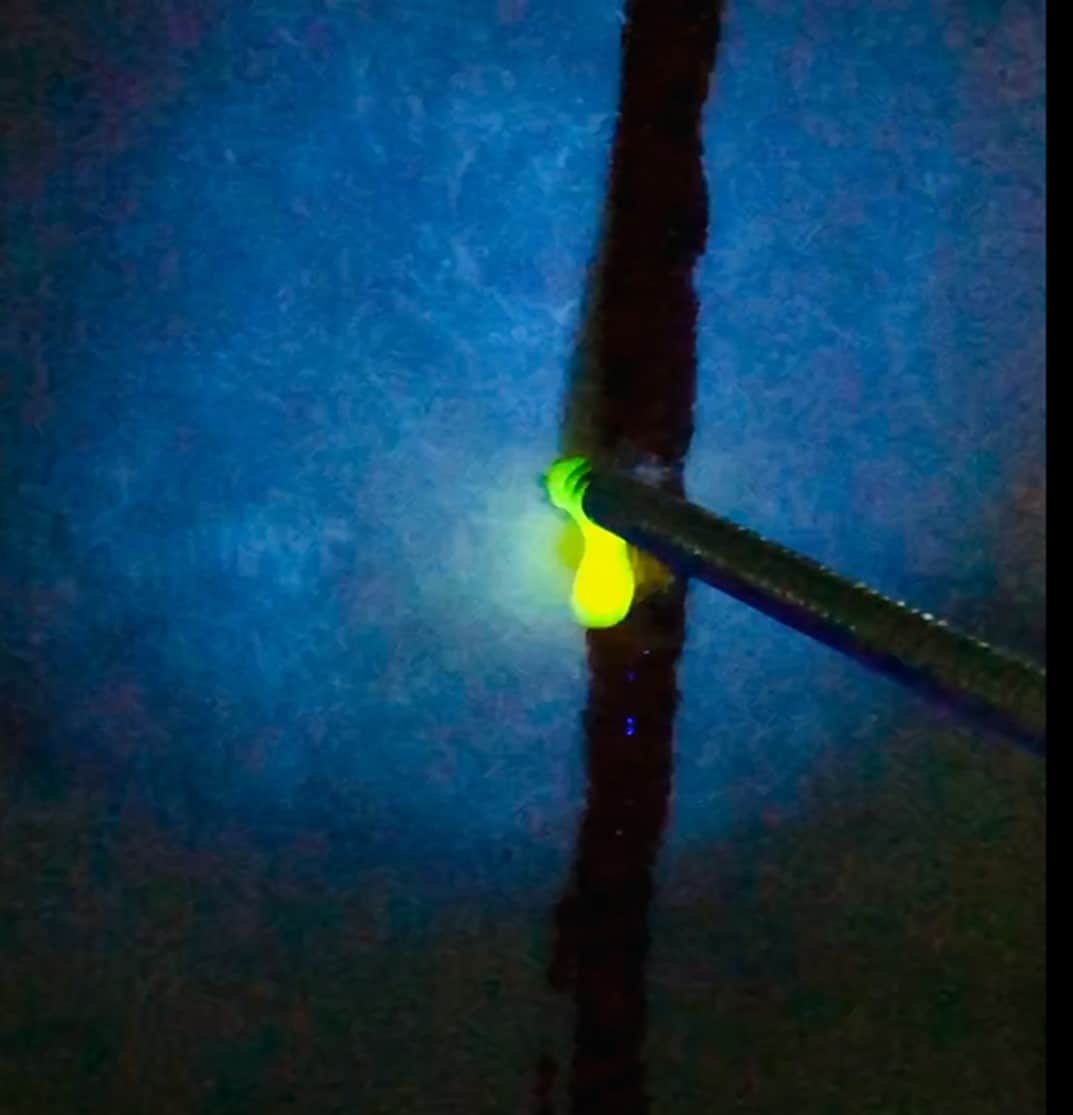

In the case study that follows, the architect changed their specification requiring the screws to be left in to one calling for the fluid-applied hole sealing system that is described. The interior drywall was going up before the lath, so the shiners could not be seen or sealed from the inside. The exterior sealing method described below has significant utility even if the interior drywall is not up. As anyone who has done it knows, finding shiners and sealing them from the inside is highly problematic. The space is often poorly lit, and the fasteners are usually very close to the studs. With several installers outside, more than one inside spotter is needed to avoid delaying the installation of the batt insulation and drywall.

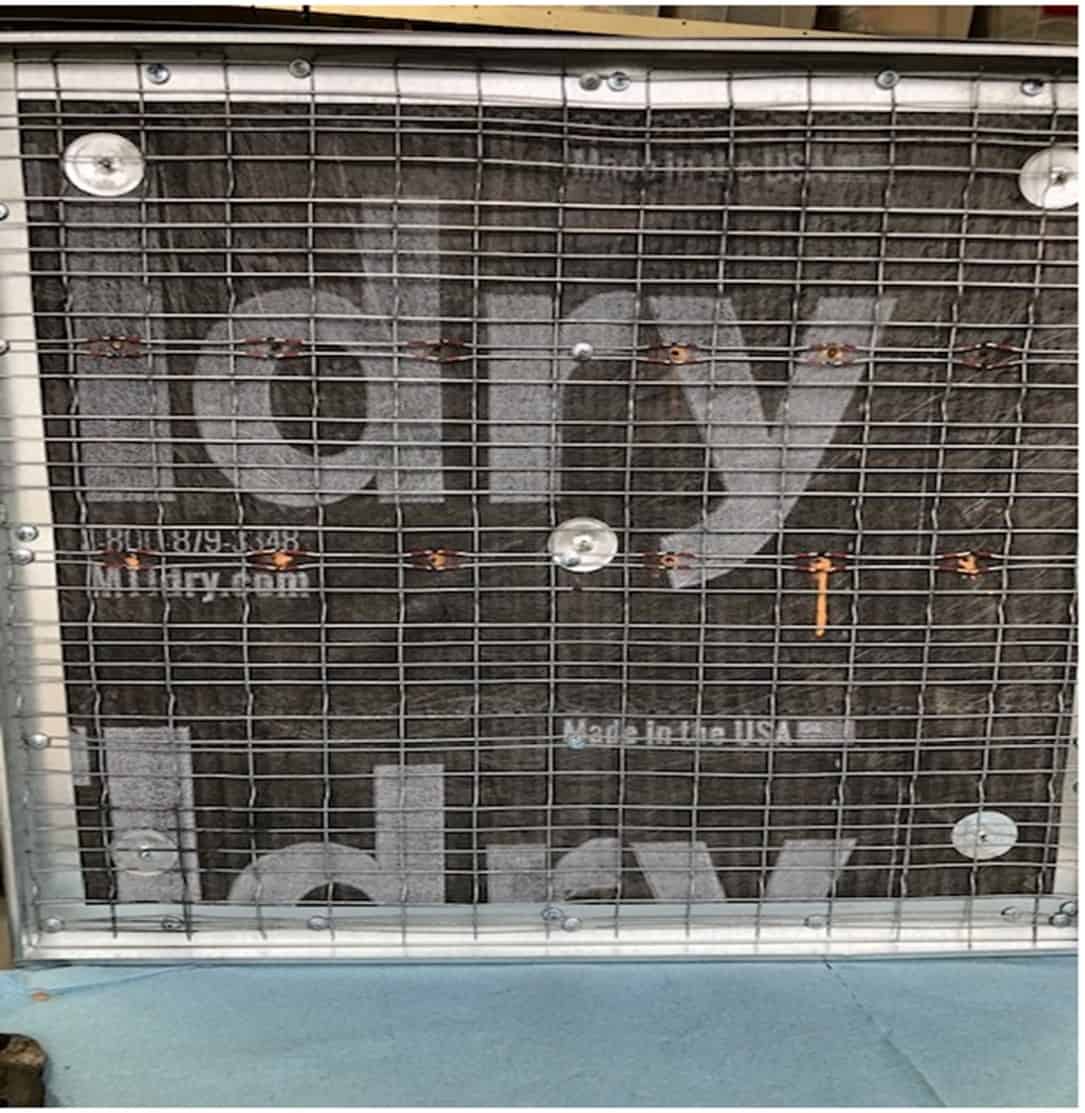

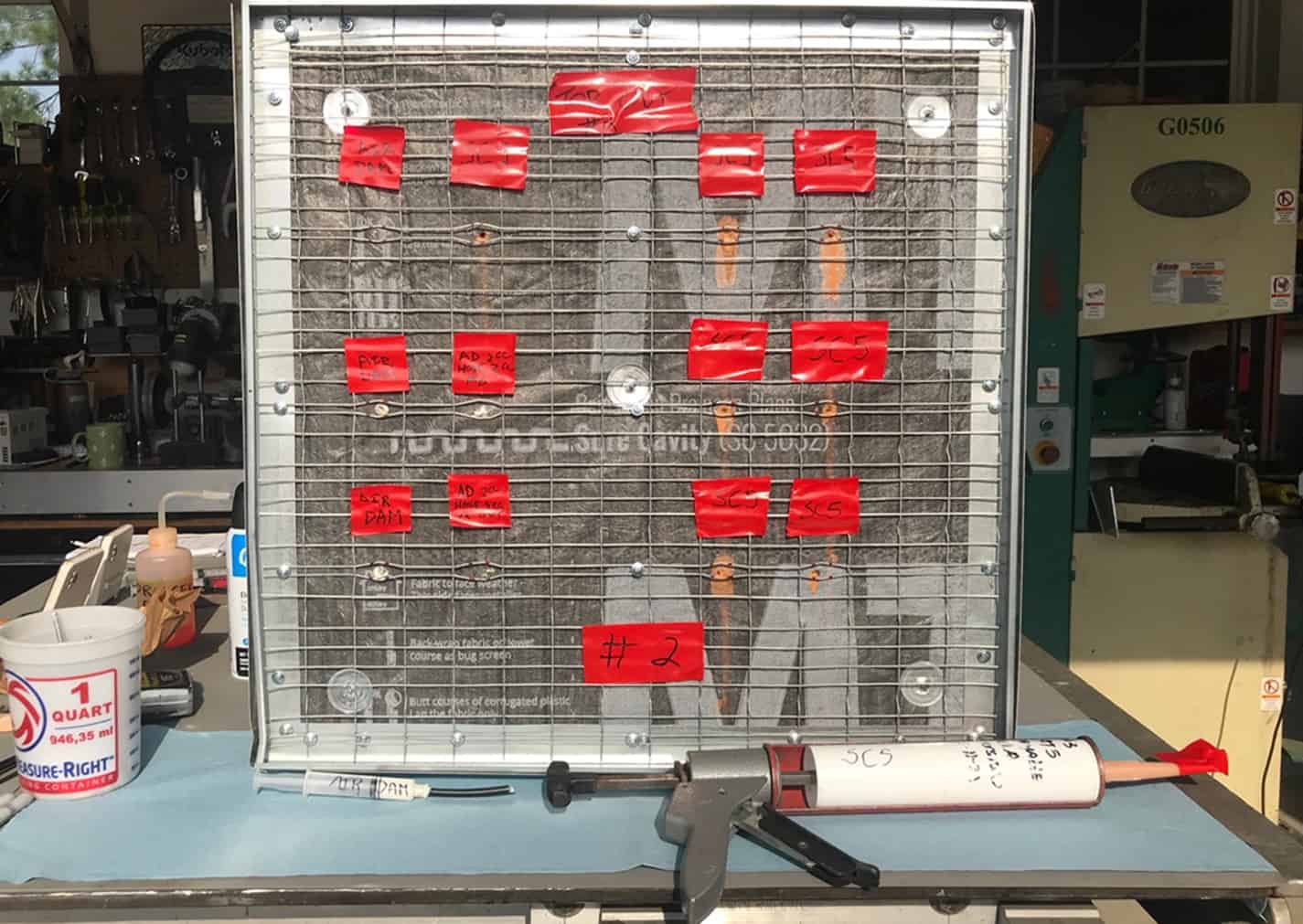

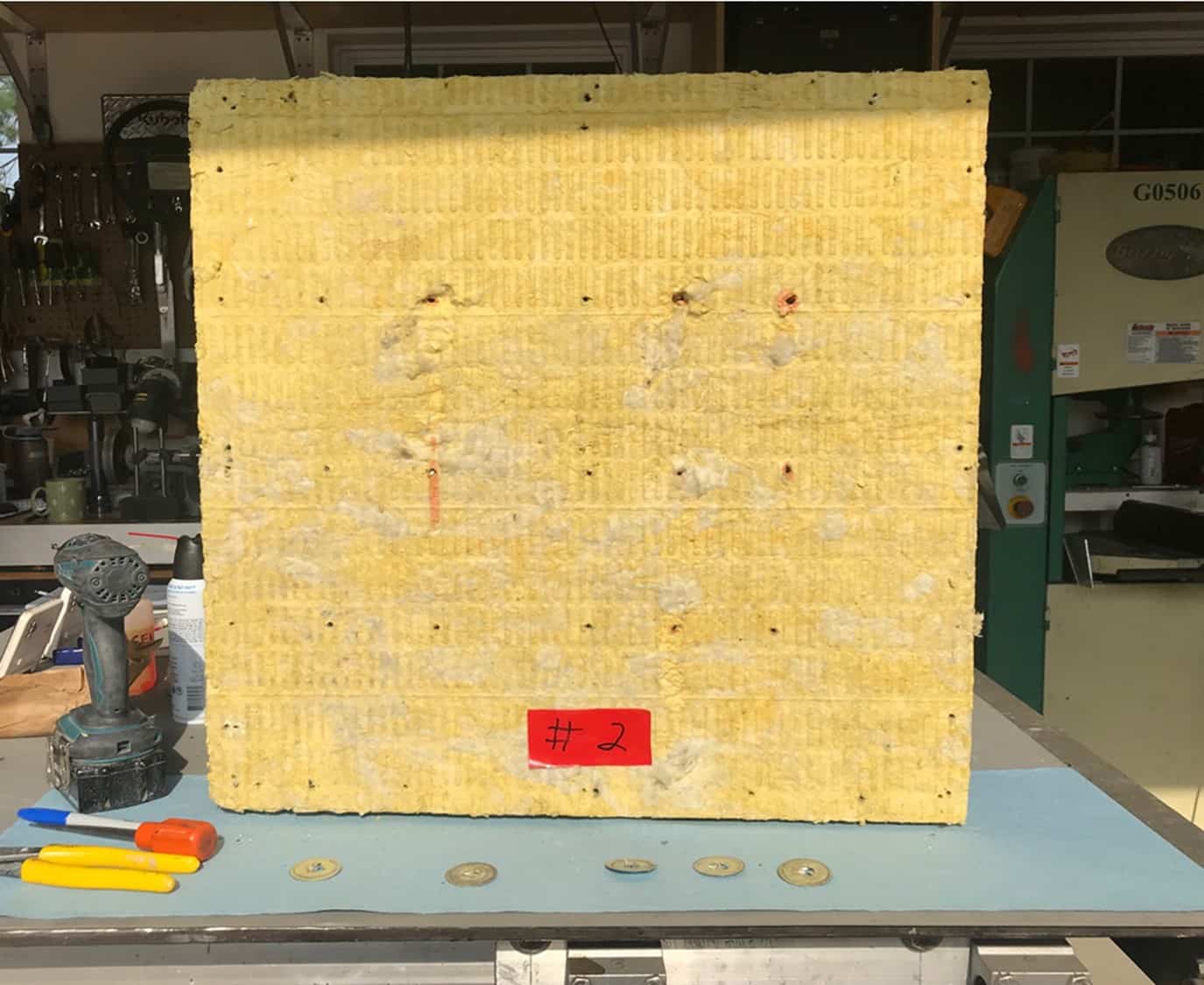

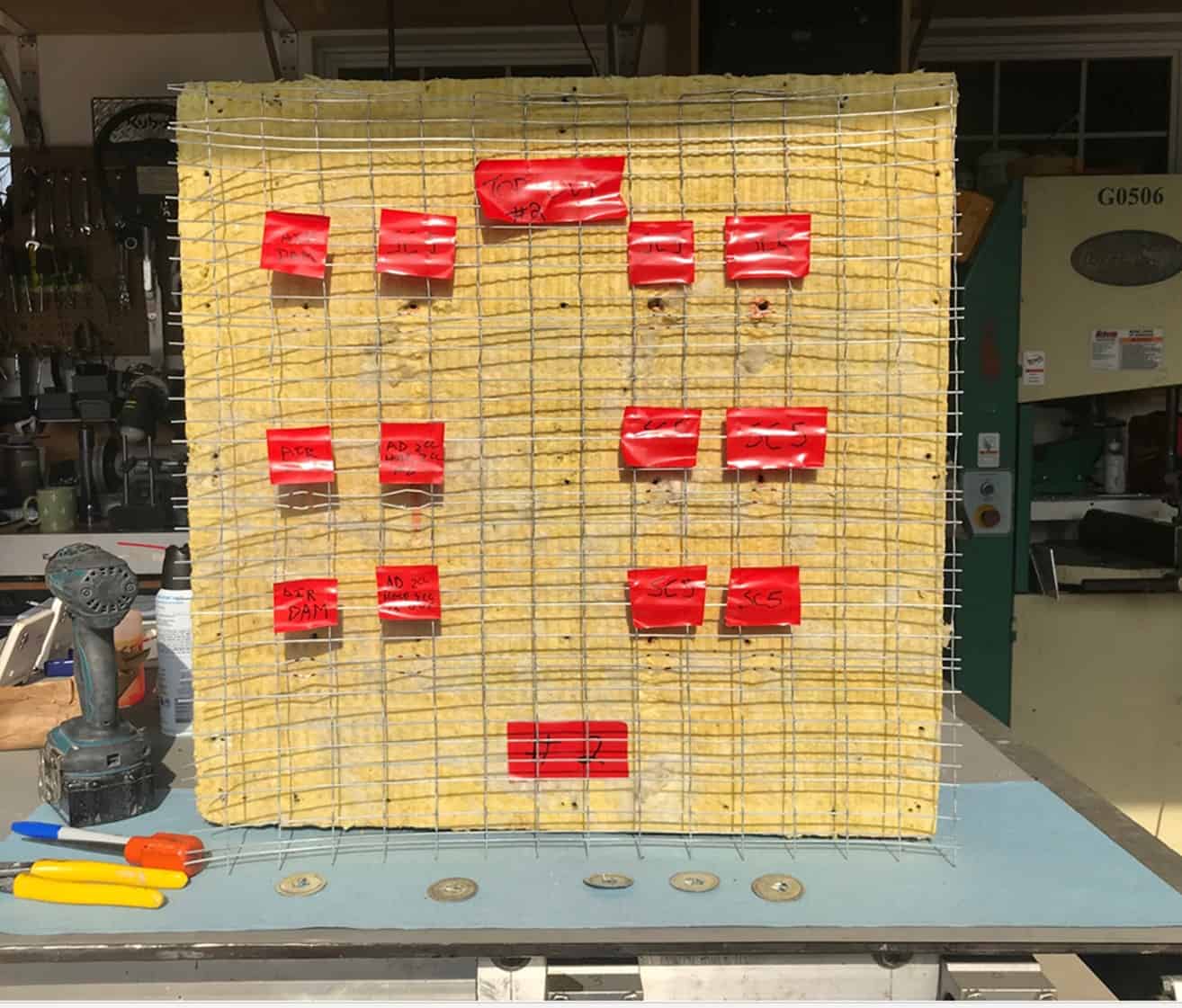

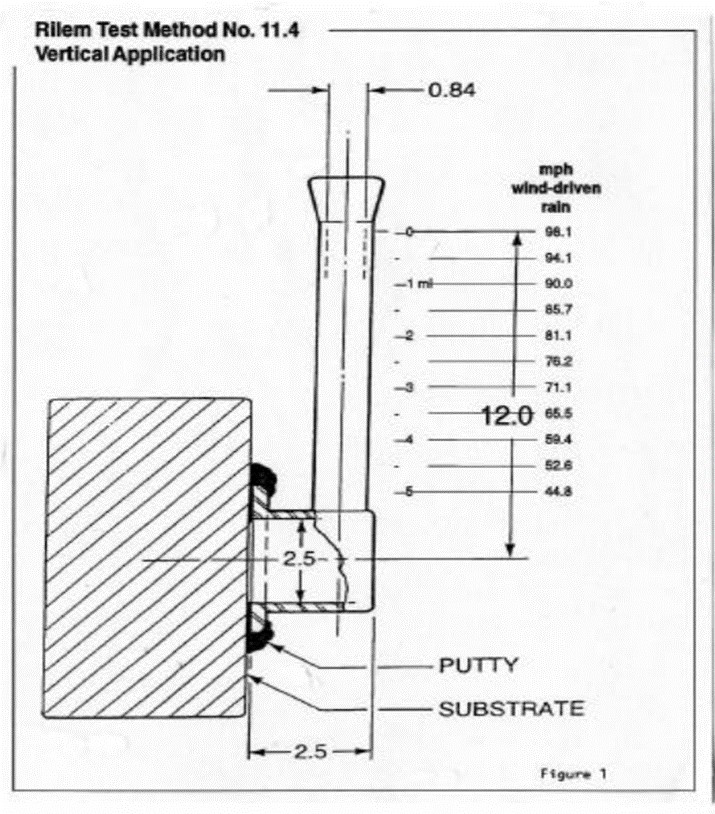

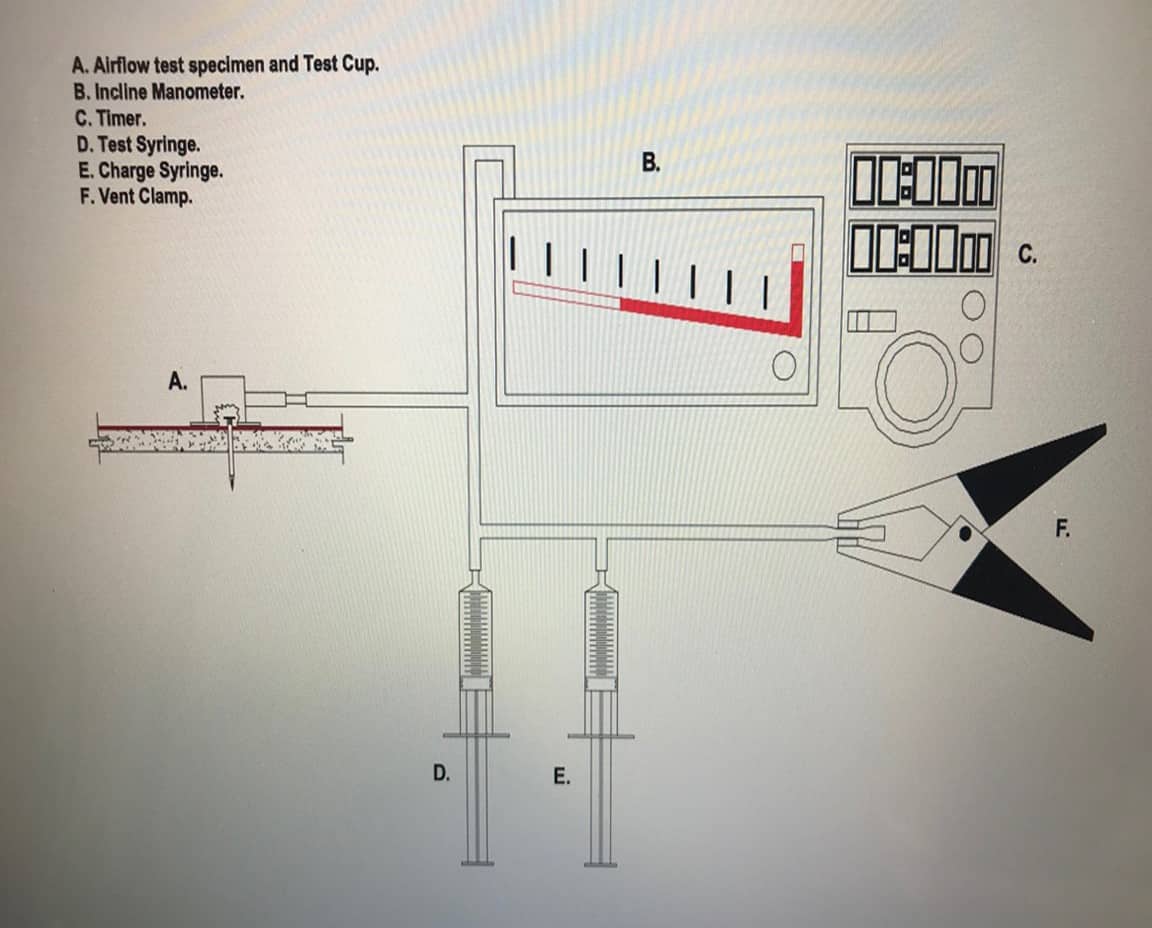

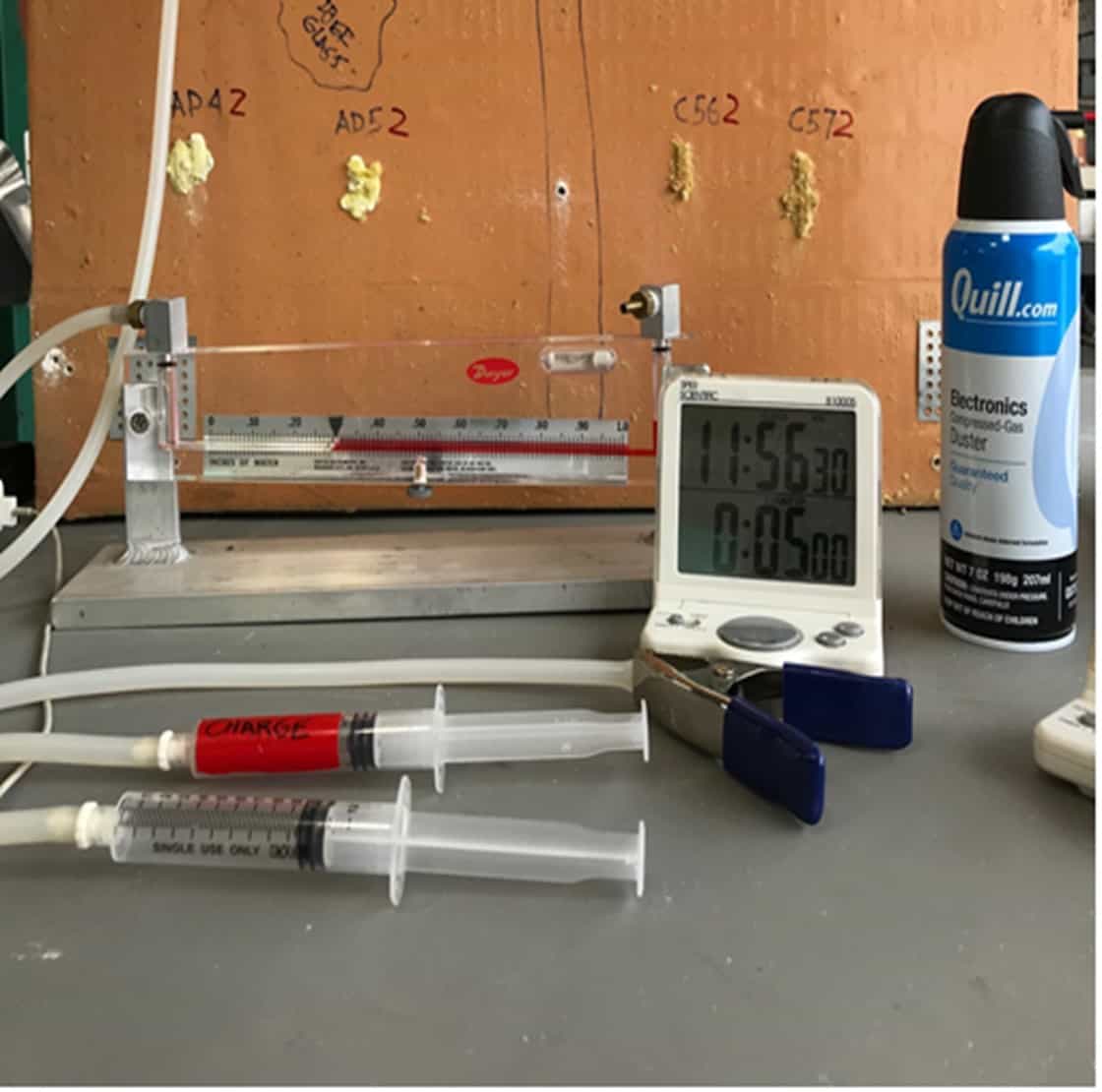

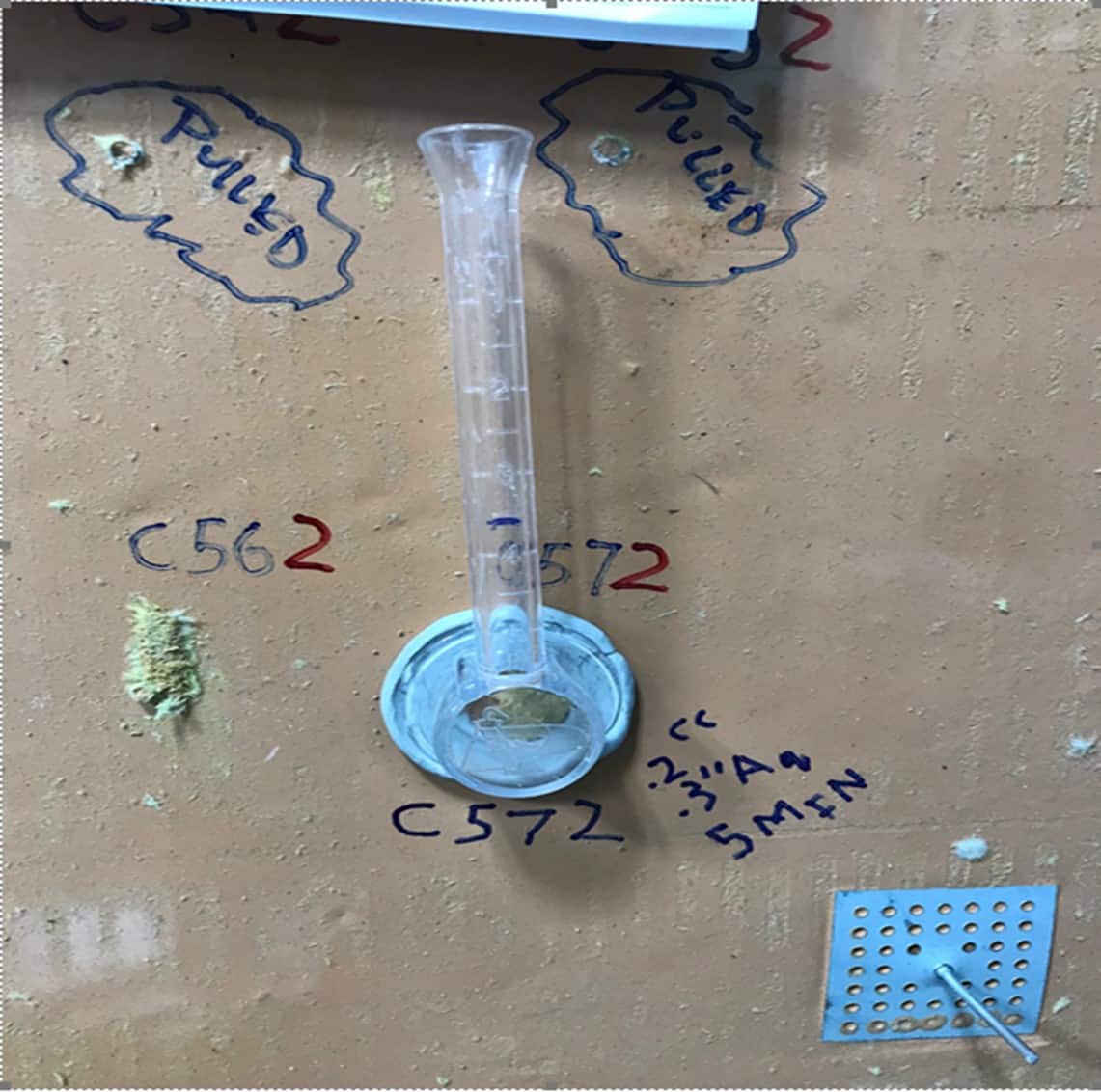

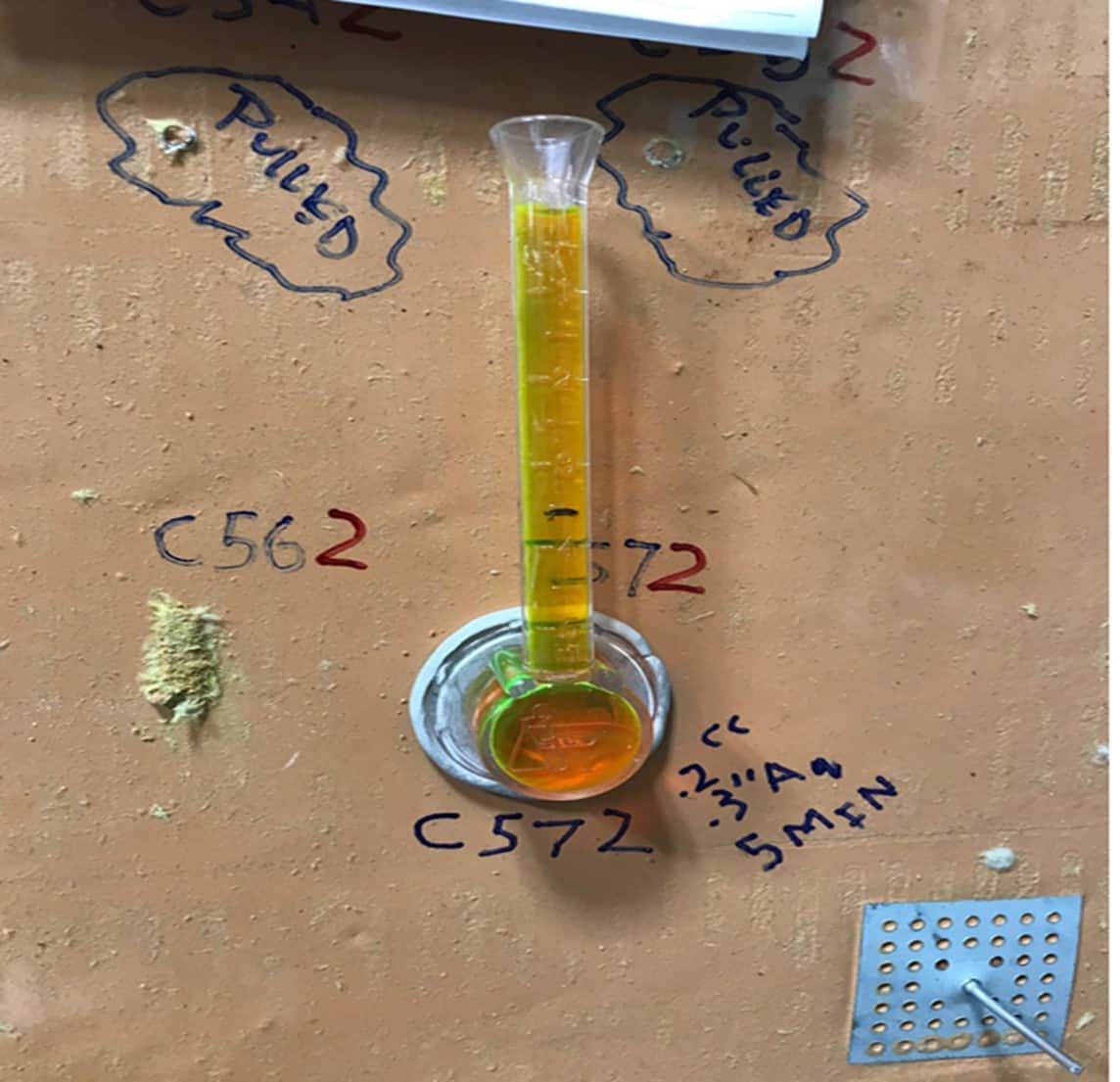

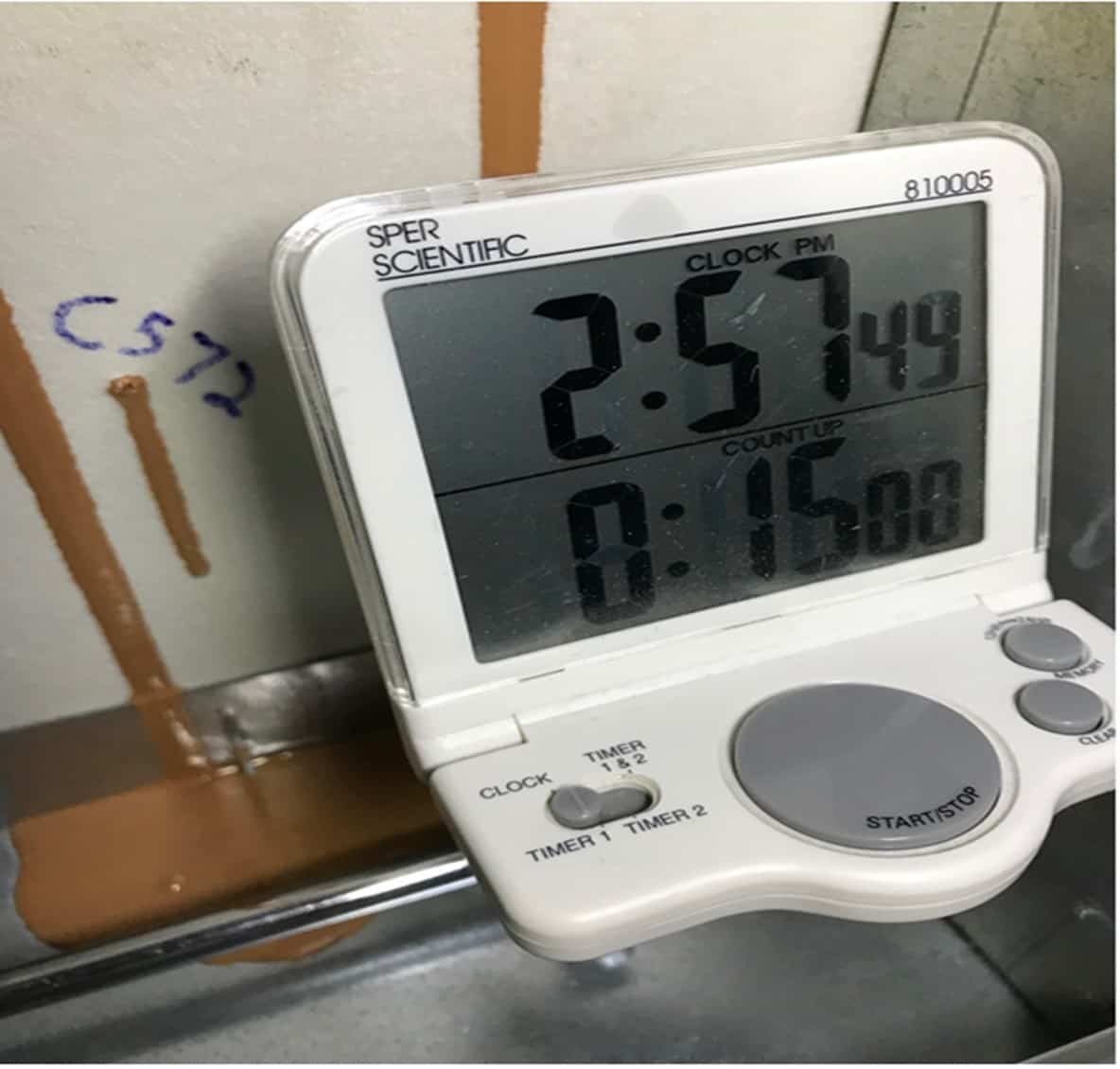

Four samples were overnighted to the testing facility in Santa Rosa Beach Florida. These mockup boards were to be air and water tested to provide a suitable solution to the problem of missing the stud with the attachment of the Structalath. See Figure 1.

In conclusion, we believe it would be best for the industry to develop equipment to help assure proper fastener placement or for contractors to spend more time or place more focus on that. However, until that happens, the system outlined here provides a path forward where previously there was none.

![]()