Today, hundreds of thousands of tourists and commuters visit Grand Central Terminal daily. Kids cheer in delight as their parents snap photos of the famous sky mural or pristine white sculptures and decorative details. When standing in the middle of one of the most popular tourist destinations in New York City, it’s hard to imagine that Grand Central once stood in disarray, and was even scheduled for destruction by city officials.

Grand Central Terminal has had a wild, ever-changing and at times tumultuous history since the first Grand Central Depot was built in 1871. But there is no denying its place in the history of New York City and Transit in the USA.

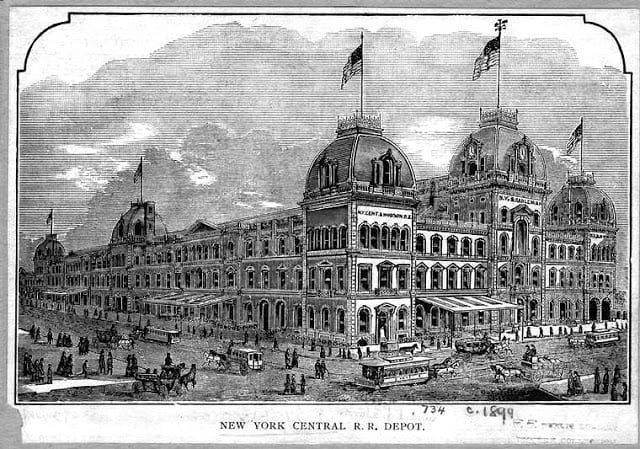

Grand Central Depot

In the early 1800’s, New York City’s economy was based primarily on water transit. Manhattan’s population and industries were located primarily on the shoreline of the island. Ferries transported supplies and some commuters from borough to borough and docks and shipyards were prime real estate. It wasn’t until the 1830’s that New York City’s first railroad was built, connecting north and Lower Manhattan.

But the first steam engines were incredibly pollutive. It led the New York City government to pass legislation in 1852 preventing trains from travelling south of 42nd St. But, train travel still increased in popularity, resulting in the need for a centrally located train depot in Manhattan.

Naturally, the developers wanted to build the station as close to the more densely populated Lower Manhattan, so they decided on a location on 42nd, the furthest south location possible under the law.

By the time Grand Central Depot opened in 1871, three railroad companies were serving New York City and were eager to expand. The structure, funded by business magnate Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt (Yes, the same Cornelius Vanderbilt who founded Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN,) was about 100 feet tall and more than 600 feet long. At the time, it was one of the largest buildings in New York City, and it felt even larger considering its location far away from the core of the population.

Rapid Growth

Despite the massive size of Grand Central Depot at the time of completion, the growth of the rail industry meant the station very quickly became undersized. Travelers needed more options, but the legislation preventing trains from traveling south of 42nd meant there could be no other train station. So Grand Central had to expand, and it did so in fittingly grand fashion.

Just 30 years after Grand Central Depot opened, they doubled the size of the building, but even that wasn’t enough. By the time they finished the updates, the rail industry had quadrupled since Grand Central had first opened.

The population of New York City had also grown rapidly over the same period. When Grand Central was built, it was quite a distance away from the population base, but as New York grew, the population got closer and closer. Once again, locals began to complain about pollution from the steam engines, and the owners of Grand Central decided a whole new station (one that leverages electricity) was necessary for the future.

The result of the rebuild would be the Grand Central Terminal we know today.

Designing Grand Central Terminal

Grand Central was already a crown jewel of a rapidly rising rail industry, and the railroad companies that used the station obviously wanted to make a big splash. A major design competition was held between some of the best architecture firms in the country. Ultimately, they settled on two architects — one to design the interior and one to design the grand façade. The two firms came together and formed Associated Architects, the name that would show up in all documents and history books but wouldn’t exist outside of this project.

Every detail of Grand Central was carefully examined, and the architects built the terminal to last much longer than the previous iterations of Grand Central. The interior was carefully planned with traffic flow in mind, meaning the station could handle far more travelers than was necessary at the time. Long passenger ramps allow traffic to flow smoothly from the top floor to the train platforms.

The façade was designed with three Roman triumphal arches, one for each of the three railroads the station served. The arches were intended to mirror the triumph of the rail industry as a whole.

The final feature of Grand Central’s façade is the massive sculptures of Mercury, Hercules and Minerva overlooking 42nd Street. The sculpture and clock tower weren’t actually built at the same time as the rest of the terminal, it was added a year after the station opened in 1913. The sculpture, called “Transportation” depicts the origins of the transportation industry.

Interior Details

The exterior of Grand Central Terminal may be immediately recognizable for most of America, but anyone who has set foot inside knows that some of the most impressive details are in the interior. The entire building is adorned with beautiful masonry carvings, including hidden acorns throughout the entire terminal. The acorns were a family icon of the Vanderbilt family.

But some of the interior design features aren’t hidden. These features include the imposing Beaux-Arts chandeliers, plated in nickel and gold. Each is 18 feet tall, impressive even when viewing from below. The chandeliers were originally intended to be a showcase of the station’s full adoption of electricity, with the exposed lightbulbs, at the time, viewed as a more luxurious feature than crystal.

Then, of course, there’s the sky ceiling. The mural is a jaw-droppingly beautiful rendering of the night sky, complete with full designs of the constellations that litter the cosmos. The shimmering gold leaf stars and constellations shimmer in the light from the chandeliers and wide arched windows. Interestingly enough, the sky is backward (east and west are inverted.) There is no recorded reason for this, and it may, in fact, be a mistake, but it doesn’t detract from the other details of the mural.

Decline of Grand Central Terminal

Grand Central Terminal was a beacon of the transportation industry for decades. But, as technology improved and plane travel became popular and more cost effective, the rail industry began to decline. And Grand Central Terminal began to slowly decline with it.

As Grand Central Terminal became less popular, crime began to overtake its neighborhood. High costs of maintenance caused the owners of the Terminal to avoid making costly but necessary updates and even sell off as many of the surrounding buildings as possible to try and cover the costs.

But rail travel continued to drop, and soon even Grand Central Terminal fell out of favor. The limited maintenance over the previous years began to take its toll on the classic building. Layers of gunk from decades of indoor smoking built up over the ceiling painting. Water began to work its way in through cracks in the ceiling, falling on the travelers below. The iconic white façade had faded to black from pollution.

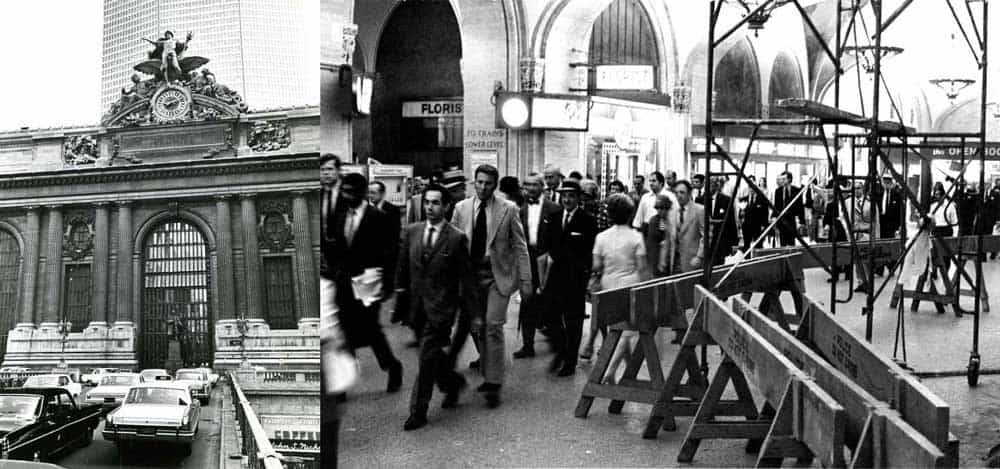

By 1970, Grand Central Terminal was in total disarray. It was no longer being used as a train station, but instead was a popular unofficial shelter for New York City’s homeless population, and was in a state of constant semi-active construction. It was rare that scaffolding wasn’t adorning the main hall, but even rarer that the projects were completed. It was only a matter of time before Grand Central became a target for demolition.

Avoiding the Wrecking Ball

The 1970’s may have been a low time for Grand Central Terminal, but the fight to save the building had been waging for almost two decades. The first recommendation to tear down Grand Central came all the way back in 1954. It was part of the initial plan the railroad companies proposed when they first encountered financial difficulties.

Instead, they began selling adjacent properties in hopes the rail market would return. It wouldn’t – at least not to where they needed it to return to be solvent.

In 1963, New York City’s other iconic train station, Pennsylvania Station, fell victim to the wrecking ball. This led to activists shifting their focus to protect Grand Central. They were successful in getting Grand Central labeled as a landmark and protected by preservation laws, but the developers and the railroad were desperate to bring it down. The impasse between the two parties led to a legal battle that would last years.

Still, in 1975 it seemed as if Grand Central Terminal would eventually be destroyed and replaced by a high-rise, high-rent office building. But Jackie Kennedy Onassis, former first lady, popular icon and noted preservationist, founded the Committee to Save Grand Central Station.

“Americans care about their past, but for short term gain they ignore it and tear down everything that matters.” – Jackie Kennedy Onassis in a letter to New York Mayor, Abe Beame – 1975

The legal battle intensified once the Committee to Save Grand Central Station became involved. Three years later, the case reached all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court would uphold the landmark status of the station, and would end any discussion of destruction of the building. Unfortunately, though, it was still in dire need of restoration.

An Icon Rejuvenated

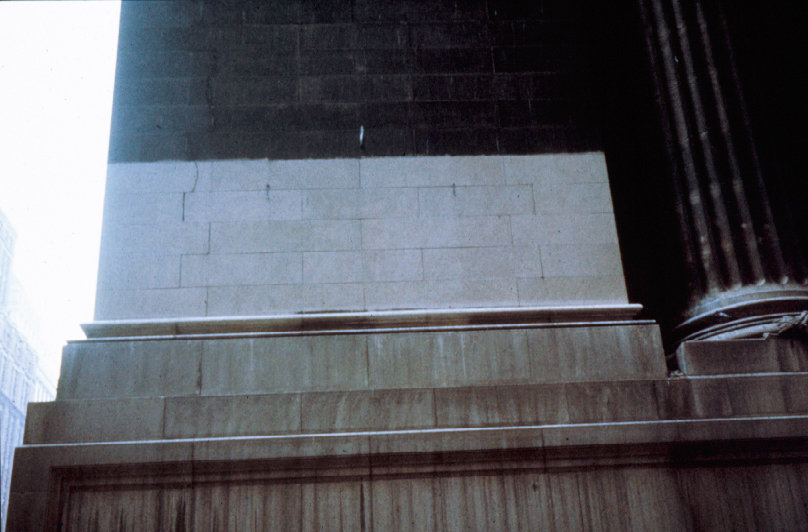

Grand Central Terminal was saved from the wrecking ball in 1978, but it still needed attention. There were multiple phases of restoration beginning with exterior cleaning in 1980. It was the first exterior restoration the building had ever undergone. It’s hard to oversell just how much pollution damage the exterior had sustained over the years, but these photos are pretty telling.

The restoration continued with a $12 million project in 1982 when the terminal was sold to new owners, but this project was mainly repair-focused. The project stopped any further decay, but wasn’t intended to return Grand Central to its former glory. Then, in 1990, the new owners, Metro-North, began a major restoration project that would turn the terminal into the tourist destination we know today.

Grand Central Today

Today, Grand Central Terminal is a perfect monument to the heights of the American railroad industry. It’s also still an active train station, proving both the industry and the building itself, have survived the low points in the history of the industry.

Grand Central is also the perfect example of why we shouldn’t be hasty with the destruction of decaying or out-of-date buildings. The building itself is far more than just four walls and a ceiling, it is an icon – a slice of early 20th century Americana in the heart of New York City. The value of the building is far greater than the value of the real estate upon which it resides. Had it been destroyed in the 1950s or 1970s, these memories would never be made.