Interior restoration cleaning benefits from a gentle approach.

They’re clean now, but in 2012, carbon and soot darkened the arched and vaulted tiled ceilings and grand expanses of limestone and travertine interior walls in what was once the home of the Chicago Theological Seminary.

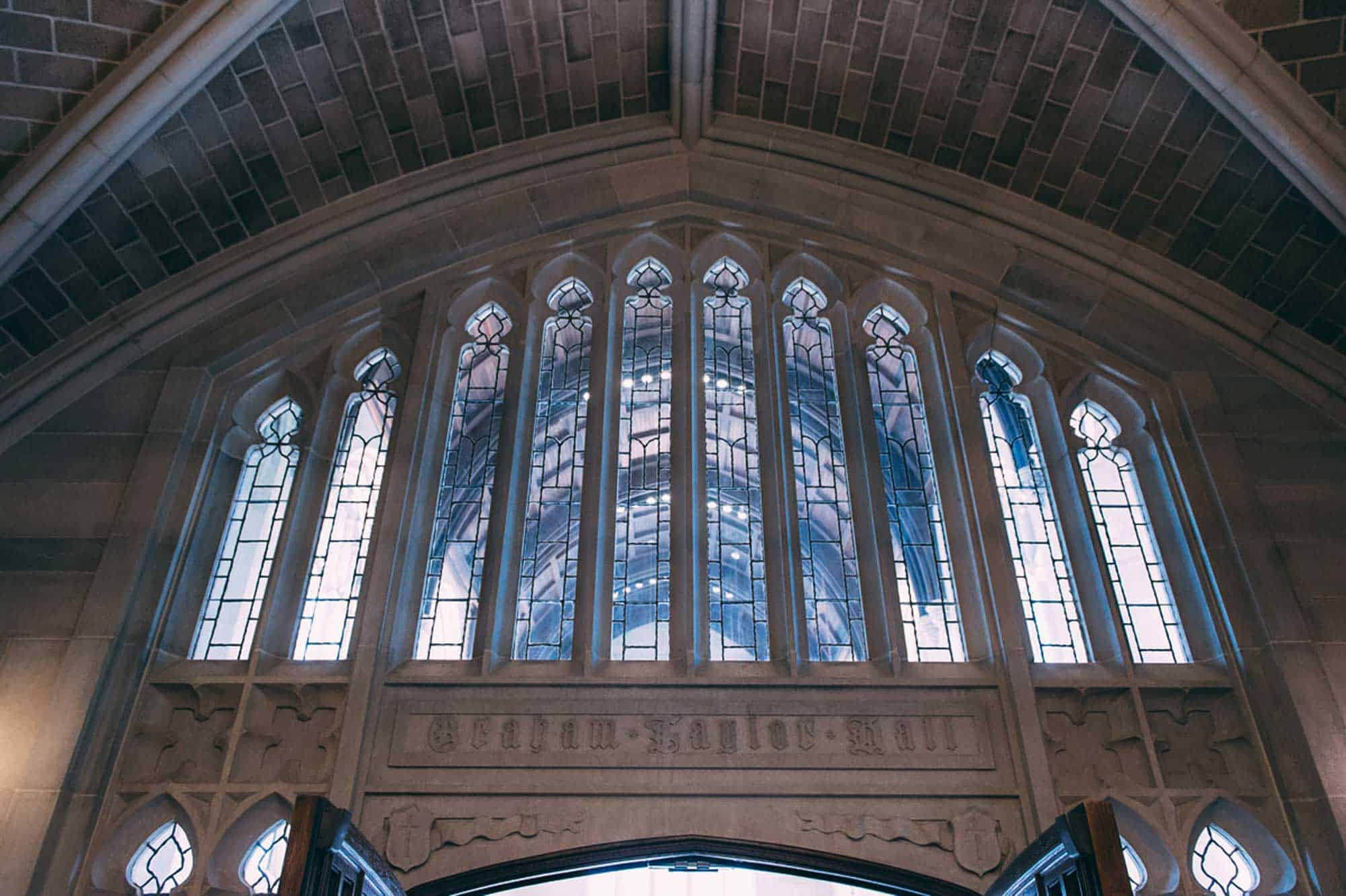

Built in 1928, the limestone and red brick Gothic revival landmark at the heart of the University of Chicago campus now houses the university’s Saieh Hall for Economics, following a two-year, $105 million adaptive reuse project.

Ann Beha Architects, Boston, walked a careful line between preserving the structure’s historic character inside and out, and renovating it to serve as a modern, high-powered learning center. The design blends nearly century-old masonry, stone and tile with contemporary metal, glass, wood and stained concrete. It combines historic context and 21st century building performance.

Masonry cleaning was central to both, revealing that context and prepping it for needed repairs, renovation and rehabilitation.

The project’s masonry contractor, Bulley and Andrews Masonry Restoration, Chicago, tapped Midwest Pressure Washing and Restoration Inc., Griffith, Ind., to conduct the detailed, precision cleaning of the 150,000-square-foot building’s sensitive interior and exterior surfaces.

The Midwest Pressure Washing and Restoration crew used an extended period of water-soaking to remove dark atmospheric staining from the venerable building’s intricate brick and limestone exterior. While chemical pressure-washing or abrasive cleaning might have been faster, the team wanted to use the gentlest means possible on the historic exterior fabric, said Don Zuidema, the company’s president.

Cleaning approximately 50,000 square feet of interior masonry was trickier. Though much of the decorative interior’s surfaces were nearly as dirty as the exterior, the volumes of water needed for water-only cleaning or traditional pressure-washing could easily flood and damage the inside spaces.

Also, the aggressive masonry restoration cleaners typically used to remove carbon and soot from exteriors could etch and stain Saieh Hall’s sensitive interior stone, brick and tile.

Avoiding that kind of damage, while freeing the interior from decades of soot and carbon soiling and staining, was a key objective, Zuidema says.

The Midwest Pressure Washing crew began by carefully testing more than 30 products on the complex range of interior surfaces, which included clay brick, limestone, travertine, and ceramic tile.

“PROSOCO’s EnviroKlean® 2010 All Surface Cleaner worked remarkably well,” Zuidema said. “It cleaned as well as anything we tested. It’s also a mild product. Preservationists and architects like how it’s safe for the substrates and nearby surfaces.”

According to its product data sheet, the product, a multi-use cleaner and degreaser, contains no harsh acids, caustics or solvents.

Nevertheless, taking no chances, the Midwest Pressure Washing and Restoration crew made sure to isolate cleaning areas with plastic and tape everywhere they worked.

“We used All Surface Cleaner on about 85 percent of the interior cleaning,” Zuidema added.

In general, cleaning operations began with brush-application of clean water to dirty surfaces. This “prewetting” helps keep the cleaner on the surface where it does its job of dissolving the contaminants.

The crew members applied the All Surface Cleaner to the wetted substrates carefully and locally, using gentle scrubbing with soft brushes.

The nearly 100-year-old masonry required soft brushes to preclude any chance of damage. But the fact that the crew could use soft brushes is a testament to how well the cleaner dissolved the contaminants, Zuidema said.

“The cleaner did most of the work,” he said. He added that it was particularly useful on the thousands of square feet of travertine walls in former chapel spaces. There, the technicians were able to release soiling from inside the porous substrate’s countless nooks, crannies and holes — without the usual methods of hard scrubbing or flushing with large volumes of high-pressure water.

After about a 5- to 10-minute dwell, Zuidema said, they rinsed the spent cleaner and the dissolved grime with low-pressure, low-volume water. The crew immediately vacuumed up the water into collection tanks. They used pH strips to ensure the collected rinse water was pH-neutral before release to the sanitary sewer.

“That’s another good thing about All Surface Cleaner,” Zuidema said. “It’s mildly alkaline, but by the time it has done its work and has been rinsed off, it’s very close to neutral.”

The vaulted tile ceiling of the cloister, a main passage extending nearly the length of the building, provided a particular challenge. Just to get to the ceiling, the team had to erect scaffolding. Then the scaffolding had to be completely tented in plastic to keep water from dripping and splashing into the space below during cleaning.

“You don’t want anything leaking in a building as priceless as this,” Zuidema said. “Not even water. In addition, you’ve got other trades installing their own material. That has to be protected, too.”

Other trades included Bulley and Andrews Masonry Restoration, whose masons repointed 100 percent of the hall’s 100,000-square-foot exterior. The interior needed less attention — mostly miscellaneous tuckpointing and limestone dutchman repair in the cloister and several chapels, said company president Chris Lee. Masonry needed spot-patching throughout the building, and one doorway needed its stone jambs entirely reset.

Preliminary cleaning with 2010 All Surface Cleaner helped the architect and masons identify the areas needing repairs.

“That first cleaning made it easier to find hairline cracks or stones with bad corners,” Lee said. “There was a lot of dirt in there.”

The Indiana limestone surrounds on the cloister hall’s several dozen arched windows looking out to the exterior provided one of the most dramatic before-and-after effects. “They went from black to looking almost new,” Zuidema said.

That surprised Zuidema. “When they wanted to try 2010 All Surface Cleaner, and I saw how dirty that stone and brick was, I had my doubts,” he said. “It’s a mild product — we use it to wash our vehicles — but it tackled decades of moderate to severe staining on historic masonry.”

The detailed restoration cleaning and repair helped execute a design that garnered a 2014 Honor Award for Excellence in Planning from the Society for College and University Planning. The project also won a 2014 Honor Award for Design Excellence from the Boston Society of Architects — hard evidence that a soft approach works.